Level Crossing Safety

Network Rail says it is significantly reducing risks at railway level crossings. But the company remains tainted by allegations of a ‘cover-up’ over the deaths of two young people at a crossing in 2005.

Letting children skate

on thin ice

Level crossing safety after Elsenham

Researched and written by Paul Coleman

*

*

CONTENTS

P*

1: Saturday mourning: Two teenage friends set out to take a train from a railway station with a long history and a very unusual layout.

2: Network Rail and level crossings: Network Rail is responsible for the safety of Elsenham station’s footpath level crossing.

3: Happy and excited: The two girls buy tickets. Trains approach. But tragedy follows.

4: Grief and anger: Elsenham’s footpath crossing is a ‘bear trap’. Experts also say the crossing still poses great dangers to users.

5: Network Rail – the company: The girls’ families encounter Network Rail, the ‘hybrid’ organisation responsible for railway safety.

6: RSSB investigation: The Rail Safety and Standards Board publishes the findings of an investigation into the Elsenham fatalities.

7: RAIB investigation: Rail accident investigators publish their analysis of the Elsenham fatalities.

8: Inquest: A jury at a Coroner’s Inquest hears from witnesses and safety officials – but some evidence is not heard.

9: Grayrigg: Network Rail apologises for the Grayrigg derailment and fatality. Meanwhile, Network Rail settles civil actions over Elsenham.

10: Hudd and Hill: Anger flares as ‘whistleblown’ documents show Network Rail knew long ago Elsenham’s footpath crossing was dangerous.

11: Who knew? Who knew about Elsenham’s dangers before the fatalities occurred? Allegations of a ‘cover-up’ fly.

12: “Spinning plates”: Network Rail pleads guilty to health and safety charges over Elsenham. Network Rail closes level crosses across the UK.

13: Thin ice: Network Rail is fined over Elsenham as cover-up allegations linger. Another young person is killed in similar circumstances.

14: New safety measures: Network Rail seeks to reduce level crossing risks with a new team as new safety technology emerges.

15: Inquiry by MPs: MPs hold Network Rail officials to account by MPs for the company’s ongoing record on level crossing fatalities and safety.

16: Closing level crossings: Network Rail continues to close level crossings but the rail regulator remains unsatisfied.

17: A new era? – Does Network Rail’s debts and lack of public accountability continue to compromise level crossing safety?

18: A ‘sorry’ apology: MPs publish their level crossing safety report. Network Rail apologises for the way it has treated victims’ families.

19: An Elsenham legacy: The Elsenham fatalities bequeath both a legacy of injustice and of level crossing safety enhancement.

20. Postscript Elsenham – Personal reflections on how the death of two teenage friends changed not only a railway station but rail safety culture.

Resources

**

PART 1: SATURDAY MOURNING 1. Saturday, 3 December 2005. 2 Elsenham station (2005) 3. A rural station 4. Crossing the railway 5. Level crossings 6. Footpath crossings 7. Risk and personal responsibility 8. Footpath crossing gates 9. Sighting times, distances and curvature 10. Staggered platforms 11. Miniature Warning Lights 12. Yodel alarms 13. Crossing keeper 14. Signalling 15. Station buildings 16. Up line Platform 1 17. Down line Platform 2 18. Buying tickets 19. Level crossing sequence (2005)

Saturday mourning

1. Saturday, 3 December 2005

Rewind to 3 December 2005. It’s one of those relaxed Saturday mornings that older children enjoy, especially after a week of teachers, homework and school.

Intermittent cloud interrupts bright mid-morning sunshine but the cosy promise of Christmas looms brightly.

Two young friends, Olivia and Charlotte, cheerfully embark on a shopping trip to buy Christmas gifts in the famous English university town of Cambridge.

Earlier that week, Olivia and Charlotte have planned their Saturday morning adventure on their computers. The friends have messaged each other via MSN, the online instant messenger service.

Both Olivia and Charlotte attend Newport Free Grammar School. Olivia began her education at Little Hallingbury Church of England primary school. Charlotte started at Henham and Ugley, another Church of England primary.

Born on 28 November 1991, Olivia, aged 14, is slightly older than her friend Charlotte. Popularly known as ‘Liv’, Olivia loyally remains in contact with several friends from her junior school days at Little Hallingbury.

‘Liv’ charms everyone with her smile and cheerful greeting, say her family. She likes to joke but never maliciously – and often laughs at herself too. Olivia shows early signs of being a budding TV reporter. She also swam with dolphins in 2003.

For Charlotte, born on 10 March 1992, today represents a change to her normal Saturday morning routine. Every Saturday for the past six months, Charlotte, aged 13, has got up early to go and work with her father, Reg, for her Uncle Davy’s wholesale delicatessen business.

Charlotte, or ‘Charlie’, as family and friends affectionately call her, proves to be a diligent co-worker. By December 2005, Charlotte has earned and saved enough money to go Christmas shopping.

Charlie is ‘vivacious, beautiful and generous,’ say her family. Charlotte likes theme parks – and writing poetry. In 2004, Charlotte writes in a card for her father: ‘I love you Daddy more than an infinite number of giant buffalos charging.’

*

**

2. Elsenham station (2005)

It’s 10.30am. Olivia and Charlotte reach their local railway station at Elsenham on this dry and mild Saturday morning. On weekdays, Elsenham station bristles with determined commuters. On Saturday mornings, like today, the platforms breathe more easily.

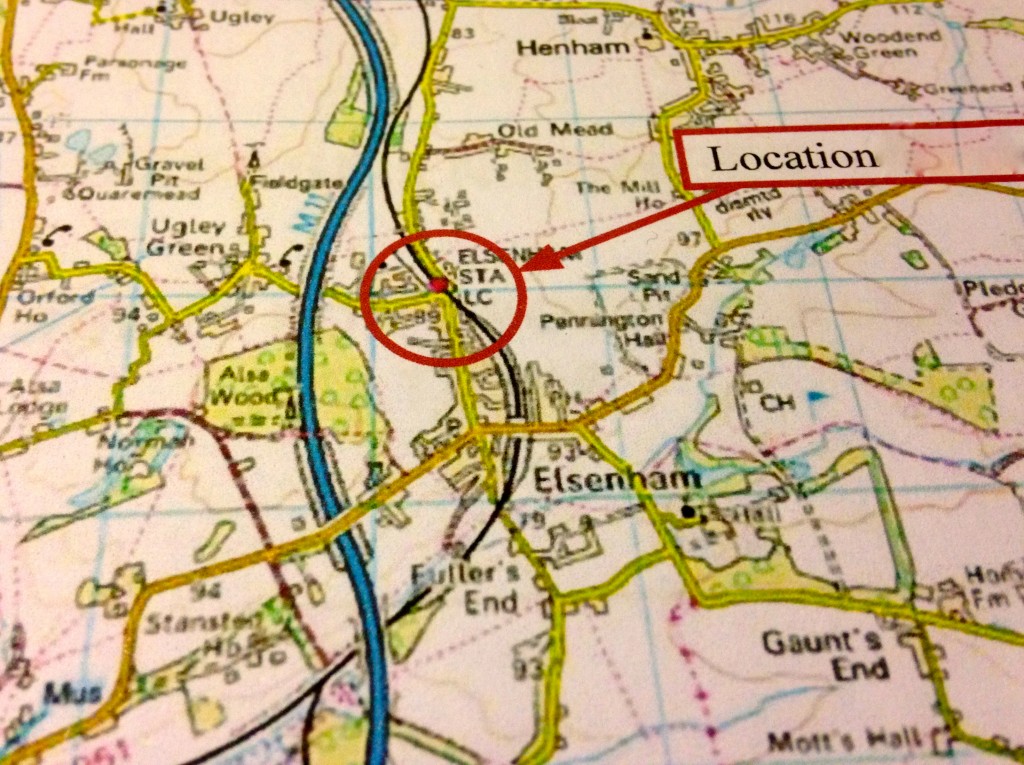

The station serves the small yet growing village of Elsenham, set in rural undulating Essex countryside, 30 miles (53 kilometres) north of London and 20 miles (32km) south of Cambridge. The railway and station sits between the village’s main development of houses and streets to the west, and an expanse of mainly open, cultivated tree-lined fields to the east.

The station lies on the busy West Anglia Main Line, one of the UK’s main rail arteries, that serves London Liverpool Street – a major central London commuter terminus – and other stations including Audley End, Bishop’s Stortford and Cambridge. An eastward branch to the south of Elsenham carries air travellers to and from Stansted, one of London’s five international airports.

Two railway lines, an Up and a Down line, run between Elsenham station’s Platform 1 and 2. Both platforms can accommodate trains up to eight cars long.

Platform 1 serves Up line trains calling at Elsenham on their way south towards Stansted Airport and London Liverpool Street. Platform 2 allows passengers, like Charlotte and Olivia, to board trains heading north on the Down line towards Cambridge.

*

3. A rural station

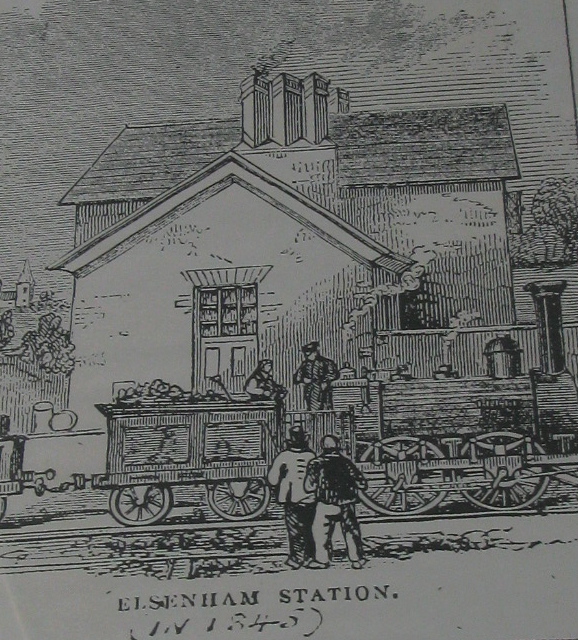

Elsenham station originally opened in 1845. The station’s rare and unorthodox layout of platforms and buildings owes much to the quainter rural railways of a sleepier yesteryear – when slower trains operated less frequent services serving smaller Elsenham populations.

Elsenham typifies an English countryside station. Steam train services once passed through Elsenham. In April 1993, the station pays homage to its past by hosting a steam engine gala. Amateur film footage shows hundreds of local people flocking to the bunting bedecked station. They admire chuffing steam engines and chugging vintage cars and lorries in the station’s nearby car park. Children sit and ride a miniature Great Western steam engine in an adjacent field. A fairground organ pipes cheery tunes.

In the early 21st century, 25kV overhead wires, suspended over the tracks, supply electric power to multiple unit passenger trains via train pantographs. Some multiple unit passenger trains use diesel, as do hulking freight trains.

Electrification enables more frequent and faster trains to stop at Elsenham and others to pass through. Each weekday and Saturday between 0630 and 0830hrs, 19 train movements occur at Elsenham, according to the timetable operative to 10 December 2005. Twelve are Up trains, five of which stop and seven pass through on their way south to Stansted or London. Of the seven Down trains, four stop and three go through on their way north to Cambridge.

The maximum speed for multiple unit passenger trains on this two-track section is 70mph (113km/h).

Some 172,500 journeys are made from Elsenham station during 2005, according to ticket sale records. This represents a 25,000 fall in sales since 2003. Season tickets form about two thirds of sales.

The overall number of people travelling from Elsenham is falling but large numbers of school children and students, en route to and from schools and colleges in Newport, Cambridge, Stansted Mountfitchet and Bishop’s Stortford, frequently use the station.

They include Olivia, who is familiar with the station as she uses it weekdays on her way to school.

*

4. Crossing the railway

In 2005 passengers completing a return journey from Elsenham will walk across the railway lines at least once. Some may walk across more than once.

For instance, a Cambridge-bound passenger without a ticket, walking from the village in the west, needs to walk across the tracks to reach the ticket office on the Up platform. She buys a ticket and crosses back over the tracks to the Down platform to wait for her Cambridge train.

Similarly, passengers like Olivia and Charlotte must cross the tracks to buy a train ticket. The Up platform is the only platform offering ticket sales via a booking office and a ticket machine.

In another instance, a London-bound commuter already with a ticket parks his car at the station car park on the eastern side of the station. He approaches the Up line platform and walks across the railway tracks to purchase a newspaper from the small shop located on the Down platform. He then walks back across the tracks again to reach the Up platform to catch his London-bound train.

5. Level crossings

Rail entrepreneurs and engineers built the UK’s railways over many decades. Often they could not afford to build bridges or tunnels at every point the rails crossed a road. They created level crossings – where road vehicles, pedestrians and animals could cross over railway lines.

About 7,000 level crossings dot the UK railways at the start of the 21st Century. Most are private or footpath crossings. About one fifth are on public roads. Level crossings come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from simple walkways over single tracks in remote rural areas to crossings where users need to telephone a signaller to ask permission to cross.

Crossings operate in busy cities and towns. A small number are located at stations. An even smaller number are station footpath crossings for pedestrians and intending passengers.

Vehicles and pedestrians must use Elsenham station’s two level crossings to cross the railway line. Vehicles use the road level crossing. Pedestrians and intending passengers should only use Elsenham’s station footpath crossing.

In December 2005, the station still has no alternative way to cross the railway when approaching trains are signalled. No subway or footbridge is provided.

Old Mead Road to the east and Station Road to the west join at Elsenham station. Cars and lorries on Old Mead Road and Station Road trundle east-west over the tracks on the two-lane, two-way vehicular level crossing. The railway tracks are embedded in the road to allow vehicles to cross smoothly.

Pedestrians can use the road crossing but there is no pavement or barrier to separate them from cars, vans, lorries and buses. Pedestrians and intending passengers, like Olivia and Charlotte, tend to cross between Platforms 1 and 2 via the footpath crossing that lies parallel and adjacent to the road crossing.

6. Footpath crossings

The term ‘footpath crossing’ owes much to a bygone era when most people travelled ‘on foot’ or, if not, on horseback when they crossed the railway. Many UK footpath and bridleway crossings were installed when fewer trains carried far fewer people.

About 4,500 UK crossings feature a ‘public right of way’ for pedestrians. Many originated in the Victorian era. Most operate at remote and rural locations.

Just 97 are ‘station pedestrian footpath crossings’ – and Elsenham is one of just two such footpath crossings that combine non-locking pedestrian gates, Miniature Warning Lights and a single tone audible alarm.

An estimated 132,000 crossings are made at Elsenham station’s footpath crossing during 2004-05, with 60-90 per hour at peak times. Peak time train frequency at Elsenham is higher too, with nine trains per hour. The frequency of peak hour Up and Down line trains means they arrive grouped closely together.

This also means the road is closed to road vehicles for several minutes to allow clusters of closely timed trains to pass in each direction. For instance, on weekdays in 2005, between 0825hrs and 0835hrs, five train movements occur at Elsenham; two through Up trains, one through Down train, one stopping Up train and one stopping Down train.

*

7. Risk and personal responsibility

People are in no hurry to use the vast majority of footpath crossings, particularly when it is not safe to cross. But intending passengers are often in a hurry to use station footpath crossings to make sure they catch a train.

This urgency creates risk. Even so, all crossing users are expected to observe signs, instructions and warnings and take personal responsibility for crossing safely.

Risk at road level crossings, like the one at Elsenham, is tightly controlled in 2005. Full road barriers that interlock with signalling and a crossing keeper protect road traffic users.

Risk at footpath crossings, like the station footpath crossing at Elsenham, is loosely controlled in 2005. Warning lights and alarms protect pedestrians and intending passengers but pedestrian gates do not lock. Safe use of the crossing is entrusted to the personal responsibility of each user.

8. Footpath crossing gates

Stepping out onto the crossing to cross the tracks at Elsenham in 2005 is almost as easy as it must have been in 1845.

Two parallel white lines painted on the ground guide footpath crossing users over the railway.

The combined span of the road and footpath crossings across the railway is 14.4 metres (15.8 yards). An average person might take up to ten seconds to walk over the footpath crossing.

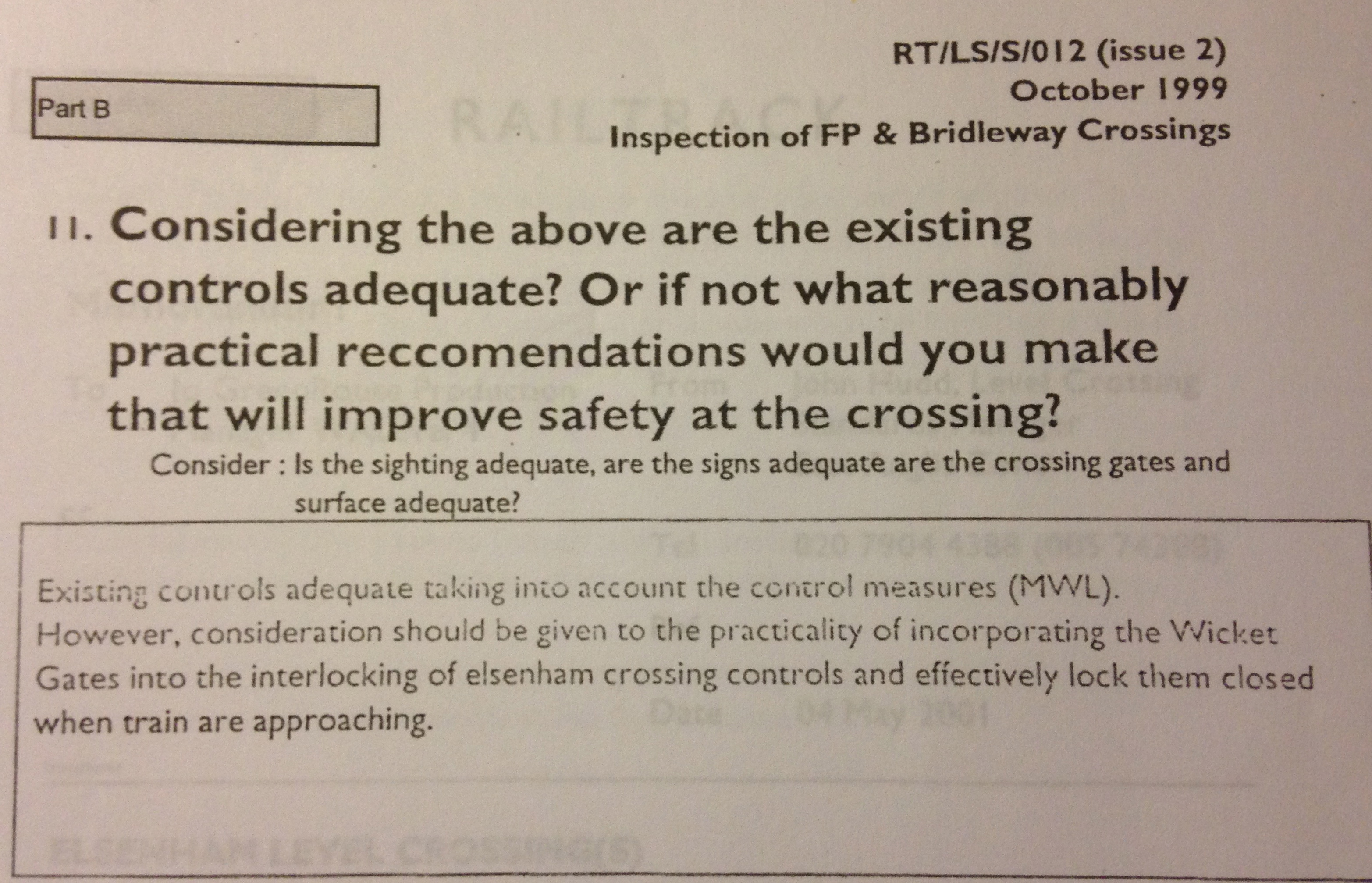

Elsenham’s footpath crossing has two pedestrian gates, one at either side of the railway. This pair of wooden, white-painted, wicket-style, pedestrian gates looks like a 19th Century remnant.

The station footpath crossing gates never lock.

Installed at some time after 1967, both the Up and Down side gates feature no locks, latches or even handles. Official railway industry standards and guidance, reissued in 1996, says: ‘All wicket gates should be easy to open from either side and be self closing. Latches which might prevent the gate being opened quickly should not be used.’

Users simply open a gate by pulling it against a spring away from the track. They can then cross the railway.

They can leave the crossing on the other side by pushing against the second wicket gate that again springs open away from the track.

Olivia and Charlotte will have to open the gates to cross the railway tracks twice. Firstly, to buy train tickets from the booking office on the Up platform, and secondly, to cross back over the tracks to catch their Cambridge-bound train from the Down platform.

9. Sighting times, distances and curvature

The course of the West Anglia Main Line bulges north of Elsenham as it runs between Old Mead Road, a river and the M11 motorway. Hence, the Main Line curves through Elsenham station.

This curvature causes a serious safety risk at Elsenham’s footpath level crossing. Pedestrians standing at the footpath crossing gate near Platform 1 experience a significantly restricted view of trains approaching on the Up line.

The officially measured sighting time elapsed between a footpath crossing user, standing at the Up side wicket gate, first seeing a fast train on the Up line and that train actually reaching the crossing is very short – about only three seconds if the train travels at 70mph.

The sighting distance is 93 metres (102 yards).

The visual warning time of three seconds from the Up platform of approaching trains travelling at 70mph is therefore far less than the time taken to cross from the Up platform to the Down side (up to ten seconds).

Furthermore, a large concrete post, supporting the eastern vehicular crossing gate, can also block that three-second view and further diminish the sighting time and distance.

This is the Up line position from which Olivia and Charlotte will have to cross the tracks to reach the Down platform opposite.

10. Staggered platforms

In 2005, Olivia and Charlotte also step towards other lurking unorthodoxies. The road and footpath crossings span the tracks at skewed angles. Users must look over their right shoulders to check and see if a train approaches on the track nearest to them.

Unlike most stations, Elsenham’s platforms are also staggered diagonally opposite each other along the curve.

The road and footpath level crossings sit at the centre of the station, between the north end of the Up platform and the south end of the Down platform.

Passengers who purchase a ticket on the Up platform must walk down a short ramp to use the footpath crossing. On reaching the Down side they then have to cross the road and walk several metres up another ramp to get to the southern end of the Down platform.

11. Miniature Warning Lights

Barriers (automated or manually operated), warning lights, audible alarms, recorded audible messages, and instruction signage ‘protect’ many level crossings in the UK.

But, in 2005, Elsenham is one of only fourteen station footpath crossings in the UK with Miniature Warning Lights (MWLs) and signage instructions.

Elsenham’s MWLs were installed in 1984, partly due to the curvature of the tracks and the shortened sighting times and distances, particularly of the Up line from the Up platform.

The warning lights and their timings conformed to Department of Transport requirements, as set out in Railway Construction and Operation Requirements documents issued at the time of installation by Her Majesty’s Railway Inspectorate, the body chiefly responsible for rail safety at that time.

12. Yodel alarms

An audible yodel alarm also ‘protects’ Elsenham footpath crossing. The single tone alarm works in tandem with the MWLs.

Illuminated green MWLs mean it is safe to cross the railway. Red lights mean it is unsafe to cross, as a train is making its final approach to pass over the crossing.

Footpath crossing users must observe the colour showing on the MWLs. The green light is extinguished and a red light illuminated – and the yodel alarm sounds – a minimum of 20 seconds before the train arrives.

The red lights will continue to show and single tone yodel to sound if a second train is due within a minimum of 20 seconds. The lights continue to show and alarm sounds until all trains clear the crossing.

But the warning lights and single tone yodel alarm do not enable footpath crossing users to distinguish between the approach of a first train and then a second train – or warn of the simultaneous approaches of Up and Down trains.

Therefore, Elsenham station footpath crossing relies entirely on users observing the lights and acting in accordance with the yodel alarm warning and fixed signage instructions: ‘Cross only when green light shows’ and ‘Cross quickly’.

The signage also gives no advice to users about the risk of a second train coming. No verbal recorded warnings are broadcast either.

Identical wicket gates, warning lights and yodel alarm are situated on both sides of the crossing.

13. Crossing keeper

The crossing keeper is based in an Up side cabin close to both the footpath and road level crossings. The purpose of the crossing keeper’s job is to ‘operate the level crossing equipment to the highest standards of safety and performance’. However, this relates specifically to the road crossing.

There is no specific mention in the job description of the crossing keeper bearing any responsibility for the footpath crossing passengers and for members of the public who use it.

Yet, in many instances, Elsenham crossing keepers warn people when they use the footpath crossing when the MWLs show red. Some keepers even try to deter people from using the footpath crossing by warning them about the £1,000 trespass fine they could incur.

The on-duty road crossing keeper controls road traffic before a train arrives. A rota of keepers controls Elsenham. Each keeper normally works an eight-hour shift: 0600-1400hrs, 1400-2200hrs and 2200-0600hrs. Two occasionally work 12-hour shifts.

14. Signalling

In 2005, Cambridge Power Signal Box controls the signalling between Cambridge and Stansted, the track that includes Elsenham. The signals are Track Circuit Block; a system that detects trains within a section of signalled track and so helps to keep trains a safe distance apart.

The railway line is divided into blocks. Each block is protected by a signal at its entrance. Train drivers respond accordingly to a stop or go indication.

This signalling interlocks with the full barrier road level crossing at Elsenham station. A signal is only cleared for a train to actually begin its approach to the station when the level crossing keeper locks the road crossing gates.

Signalling is not interlocked with the station footpath crossing gates, which are always unlocked.

A data recorder, fitted to the signalling equipment, records the timing and operation of the relays controlling the crossing MWLs, yodel alarms and the interlocking of the road crossing gates with the signalling.

15. Station buildings

Elsenham station features five small buildings. Three sit on the side of the Up line.

A grey-blue weather-boarded cabin with a flat covered gable roof, sits closest to the parallel road and footpath level crossings. This cabin houses the road crossing control panel, operated by the station’s level crossing keeper.

As mentioned, the level crossing controller operates and supervises the road crossing – but not the adjacent and parallel station footpath crossing.

16. Up line Platform 1

A short ramp leads up to Platform 1. A larger brick-built building sits next to the crossing keeper’s cabin, just a few metres from both level crossings. This building looks like a low two-storey house, with a tiled gable roof, chimney and a small side garden. It houses the ticket booking office and a larger office for the ticket clerk.

As mentioned earlier, the booking office, train ticket machines and ‘permit to travel’ machines are located only on the Up platform.

Further along Platform 1 stands another weather-boarded single storey building but with sash windows and a tiled, gable roof and central chimney. This houses the station’s waiting room. A timber canopy with an ornamental fascia, supported by cast iron columns with arched braces, provides passengers with a small amount of shelter on the long and largely exposed platform.

Track and train technology may have changed over the decades but Elsenham’s waiting room building looks like a mid-19th Century remnant. In February 1980, it attains Grade II-listed status as a building of ‘special architectural and historical interest’.

Open fields lie behind these buildings on Platform 1.

17. Down line Platform 2

The foot of the Down platform – Platform 2 – features a small shop selling newspapers, sandwiches, sweets, tea and coffee – but not train tickets. A small waiting room and a covered area sit further along the platform.

Importantly, Platform 2 has no ticket or ‘permit to travel’ machines.

Elsenham village housing lies beyond Platform 2.

18. Buying tickets

The booking office on the Up platform (Platform 1) opens Monday to Saturday, 0600-1330 hours. Passengers open a door and walk inside a small booking hall. A booking clerk sells tickets through a small window. The clerk cannot see the platforms from this position.

Two automatic ticket-issuing machines stand outside the booking office on the Up platform. The Avantix machines should operate at all times to dispense tickets to ten destinations. Passengers pay using chip and pin cards or with notes and coins.

But, according to reports, heavily used Avantix ticket machines prove unreliable.

Apparently, the Avantix machine at Elsenham is ‘out of action’ on 3 December 2005 when Olivia and Charlotte arrive at the station. Only the clerk in the ticket office can sell tickets on this particular Saturday morning.

A ‘permit to travel’ machine stands next to the Avantix machine. Users pay between 10p and £1 to buy a timed and dated token. This represents a promise to pay the right fare on the train or at the destination station.

The absence of any ticket sales points or machines on the Down platform means passengers, who walk to the station from the village, must cross the railway twice if they need to buy a ticket for a Cambridge-bound train. Passengers who join a train without a ticket risk being charged a £20 penalty fare on top of the actual ticket fare.

19. Level crossing sequence (2005)

In 2005, the level crossing at Elsenham operates according to the following sequence.

A train approaching Elsenham station on either the Up or Down lines trips a track circuit. A bell rings at the station. Two bells can ring; one for a train on the Up line, the other for a Down line train.

On hearing the bell(s), the crossing keeper walks to the road crossing. He manually closes the road crossing gates to road vehicles in order to open the railway to trains. When closed to road traffic, the barrier gates span the full width of the road on both sides of the crossing.

The keeper locks the road crossing gates and then removes one key from each gate. The gates cannot be reopened without these keys.

The keeper goes back inside his cabin with both road gate keys. He inserts each key into a control panel and rotates them to a locked position.

This stops the bell(s) ringing.

It interlocks the road crossing gates with the signals.

This interlocking means the signaller at the Cambridge Power Signal Box is now in control of the railway, including the vehicular road crossing. The signaller can now set the route for the approaching train by changing the signals to a proceed aspect. Trains can now proceed towards Elsenham station.

However, the keeper is not formally responsible for the footpath crossing. After he closes and locks the road gates, pedestrians and passengers can continue to open both footpath crossing gates and cross the railway before trains arrive – without supervision by the crossing keeper.

Generally, crossing keepers can take action if they believe individuals are exposing themselves to danger – a Rule Book duty for all railway staff. However, crossing keepers’ specific duties do not include ‘policing’ usage of footpath crossings.

A period of two to three minutes now passes, depending on the speed of the approaching train(s).

The leading wheelset of an approaching Up train then ‘strikes in’ at another track circuit 646 metres (707 yards) from the Elsenham crossing. An approaching Down train ‘strikes in’ similarly at 715m (782 yds).

This ‘strike in’ operates relays that extinguish the green miniature warning lights at the footpath crossing and illuminate the red warning MWLs. This ‘strike in’ also activates the yodel warning alarm.

Even so, pedestrians and intending passengers can still open the station footpath crossing wicket gates and cross the railway from either side.

A non-stopping Up train travelling at 70mph (113km/h) can reach the crossing from the ‘strike in’ point in 20.6 seconds. A Down train takes 22.8 seconds. Trains at lesser speeds sometimes take up to one minute to reach and pass over the crossing after a ‘strike in’. These elapsed times are in line with railways safety standards of this period.

But the time between the activation of the warning lights and alarm and the arrival of an approaching train at the crossing is not stated at the crossing on any signage.

The trailing wheelset of a train clears the track circuits immediately after the crossing. This extinguishes the red MWL. A green light is restored. The single tone yodel alarm stops – but continues if a second train is still approaching on the opposite line.

Even if another train approaches, pedestrians and intending passengers can still open the station footpath crossing wicket gates and cross the tracks. Again, this is simply because the gates do not lock.

The Cambridge signaller allows the level crossing keeper to resume control of the crossing when all trains clear the track circuit section. This permits the crossing keeper to remove the crossing gate keys from the control panel in his cabin.

The keeper takes out the keys and reemerges from his cabin. He uses the keys to unlock the road crossing gates and reopen the crossing to road vehicles.

Throughout this entire sequence, station footpath crossing users can simply swing open the unlocked white wicket gates. They can use the footpath crossing even whilst red warning lights illuminate and the yodel alarm sounds – and even when trains are seconds away from reaching the station.

PART 2: Network Rail and level crossings 1. Network Rail and Elsenham 2. Risk Management 3. Risk reduction 4. Law and ALARP 5. Risk assessments 6. Safety responsibility 7. Rail safety campaigns 8. Safety mandate 9. April 2005 risk assessment

Network Rail and level crossings

1. Network Rail and Elsenham

Charlotte and Olivia are about to use a station footpath crossing owned and operated by Network Rail, the private company that owns and operates most of the UK’s railway infrastructure. In 2005, the company is responsible for the installation, inspection, maintenance and renewal of over 7,000 level crossings in the United Kingdom.

Network Rail says ‘Britain’s rail network is a marvel of engineering’. Train travel is ‘fast, quick, efficient, reliable and environmentally friendly’.

‘Cutting edge technology’, backed by ‘exacting safety standards’ enables Network Rail to manage the UK’s rail infrastructure. ‘Rail is the safest form of transport,’ says Network Rail. ‘And we’re continually trying to make it safer.’

However, when Olivia and Charlotte walk onto Elsenham’s two platforms, enter the booking office and board a train, they are using property and equipment leased by a train operating company (TOC). Network Rail owns Elsenham station – but leases it to a private train operator, ‘one’ Railway, itself owned by the National Express Group.

As a train service franchise holder, ‘one’ Railway is responsible for the station’s commercial activities, such as selling tickets. The franchise holder also maintains and upkeeps the passenger information systems, platforms and buildings, as required by the station lease agreement.

But, in July 2004, Network Rail’s Anglia route director Jon Wiseman announces stations like Elsenham will receive new customer information systems, along with improved waiting rooms, toilets and CCTV. “Network Rail is committed to providing safe, reliable and efficient railway infrastructure,” says Wiseman. “Comfortable stations with modern facilities are an important part of our continued programme to rebuild the railway.”

Network Rail is responsible for the signalling system that interlocks with the road crossing. The company is also responsible for the MWLs, wicket gates, footpath walking surface and their maintenance.

Although Network Rail owns and operates Elsenham road level – and owns but does not operate the station footpath crossing – the company is not responsible for the users of both crossings. Users of the footpath crossing bear exactly the same personal responsibility as pedestrians crossing at a traffic light controlled pedestrian road crossing. Passengers become responsible for their own safety as soon they step off the bottom of the platform ramp to cross the railway.

However, Network Rail is responsible for assessing and managing risks posed by station footpath crossings, like Elsenham.

2. Risk management

In 2005, Network Rail has no specialist managers dedicated to assessing and managing risk at level crossings. Managers include level crossing management amongst their other rail infrastructure responsibilities.

Nine Network Rail staff, each responsible for a UK region, liaise with British Transport Police (BTP) and Train Operating Companies (TOCs) to inform young people about the risk of ‘misbehavior, trespass and vandalism’ on the railways. They visit schools, youth clubs and young offenders groups.

Personal responsibility for observing signs and warnings and for crossing safely is emphasised. Audiences for safety presentations are identified on the basis of information from BTP officers, train drivers and reports logged on the UK railway’s national incident database, the Safety Management Information System (SMIS).

BTP officers reportedly visit Olivia and Charlotte’s school at Newport, just north of Elsenham, earlier in 2005.

3. Risk reduction

A Network Rail area general manager chairs an Anglia level crossing risk reduction and mitigation group (LXRAM). This brings together representatives of TOCs, signalling engineers, maintenance engineers and BTP officers. They identify crossings where problems arise and solutions are required.

The Anglia area of Network Rail includes some 100 level crossings. The LXRAM group reviews ten per cent at any one time. Reviews consider risk assessment results, incident occurrences, incident history, and public comments and complaints.

They also review safety related incidents recorded on SMIS. LXRAM reviews a level crossing risk assessment after SMIS records three ‘near misses’, and/or after a fixed period.

In December 2005, Elsenham is included in a list of crossings for review. SMIS shows three ‘near misses’, occurring in March 2004, July 2005 and November 2005. These ought to trigger a LXRAM review but it is said no information suggests the need for an urgent review.

Typical LXRAM remedies might include installing CCTV and a BTP presence to monitor and deter ‘misuse’ of a crossing.

Tailored safety measures for specific crossing are considered. For instance, the Rail Safety & Standards Board – the UK’s rail safety research agency – quotes an example arising at some point in 2005-06, where a pair of wicket gates is ‘currently locked out of use because of misuse. An evaluation of fitting the gates with locks was under consideration’.

The specific level crossing is not named.

4. Law and ALARP

The law, as it stands in December 2005, leaves footpath level crossing users, like Olivia and Charlotte, with some formal legal protection.

Level crossings law evolved spasmodically as the UK rail system grew rapidly over many decades. Accidents often compelled reviews of level crossing law.

But potential law changes were hampered by an official view that personal responsibility must lead the way. For instance, after the Hixon level crossing accident in January 1968, a public inquiry quoted and accepted a statement from a 1957 report that stated ‘…the principle must be recognised that it is the responsibility of the individual to protect himself from the hazards of the railway in the same way as from the hazards of the road’.

The Hixon tragedy killed eleven people on-board a 12-coach Manchester-Euston express train after it collided at 75mph with a heavy road transporter carrying a 120-ton transformer across an automatic level crossing. Forty-four other people were injured, six seriously.

Later, in 1983, Members of Parliament on a House of Commons committee reported on ‘pedestrian safety at public road level crossings’. They recommended changes to visual and audible warnings and to pedestrian access layout. Again, the principle of personal individual responsibility dominated their deliberations.

The Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 applies to Network Rail. Since October 2002, Network Rail must comply with these provisions. Section 3 imposes an obligation on Network Rail to take reasonably practicable measures to ensure level crossing users are not exposed to risks to their health and safety.

This means Network Rail must assess the risks of a level crossing to all users, including people crossing and train passengers. Network Rail must put in place suitable safety measures to manage these risks down to a level that is ‘As Low As Reasonably Practicable’.

In 2005, under the Railways (Safety Case) Regulations 2000, Network Rail must also get Her Majesty’s Railway Inspectorate approval for any changes to a level crossing’s design or operation. In 2005, HMRI, established in 1840, still oversees safety on Britain’s railways through special documents. A safety case document records the safety management systems in place at each crossing – including risk assessments and measures to control risk to ‘As Low As Reasonably Practicable’ (ALARP).

Another set of documents governing level crossing safety emerges in 1996. The Railway Safety Principles and Guidance (RSPG) documents, published by the Health and Safety Executive, applies only to level crossings installed or modified after 1996, when RSPG is published. RSPG gives limited guidance on managing specific risks to crossing users, like Olivia and Charlotte, inherent at station footpath crossings, like Elsenham.

Paragraph 22 of the RSPG states ‘the choice of level crossings should avoid causing unnecessary delays to road users’. Elsenham station footpath crossing apparently met the following requirements:

- Trains passing over the crossing should not exceed 160km/h (100mph).

- Should not inhibit rail traffic frequency

- Span no more than two lines

- Possess warning times greater than the time it takes to cross

- Where MWLs are provided, the warning time should be greater, by not less than five seconds, than the time it takes to cross.

Network Rail must also ensure that the condition of gates or stiles at level crossings is consistent with The Railway Clauses Consolidation Act of 1845.

Until 2002, this patchy and often outdated legal framework is all that legally protects users from the risks of level crossings – especially, at station footpath crossings like Elsenham.

5. Risk assessments

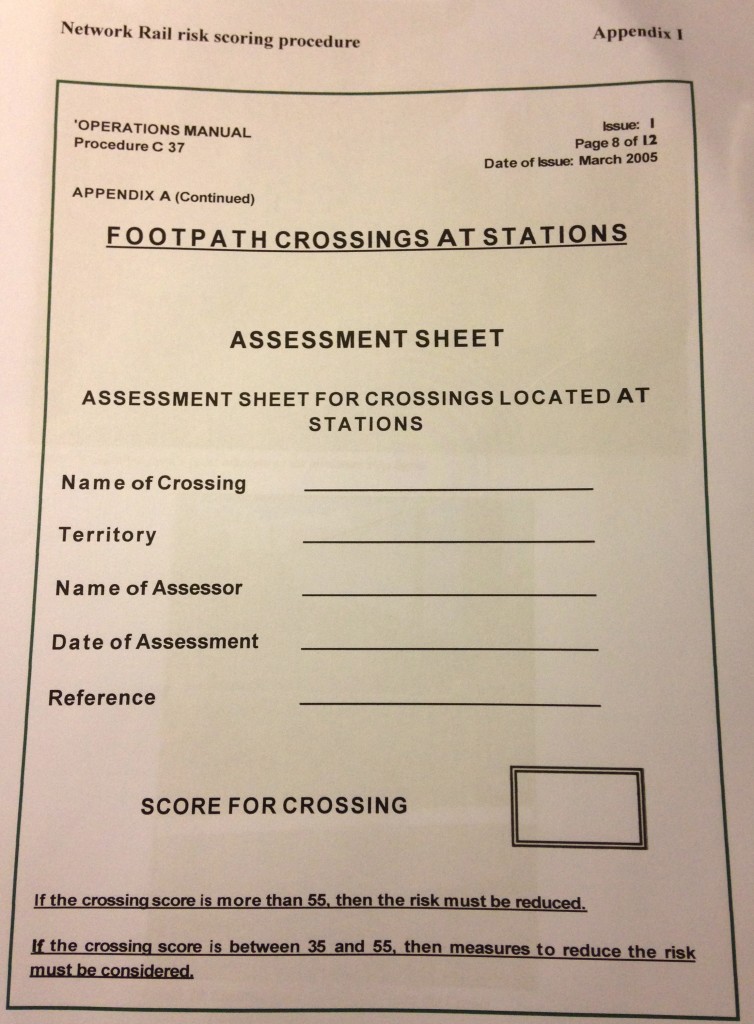

The rail industry begins to modify its risk assessment approach in October 2002. The anodyne-sounding Railway Group Standard GI/RT/7011 – Provision, Risk Assessment and Review of Level Crossings – mandates risk assessments be carried out on all level crossings.

By late 2003, a February 2004 target for station footpath crossings is clearly unattainable. Network Rail focuses on risk assessments for road crossings, which according to accident figures, pose greater risks to rail passengers. Completion of risk assessments on station footpath crossings, like Elsenham, is delayed until October 2005.

In March 2005, Network Rail revises its Operation Manual so trained level crossing risk managers can begin semi-quantitative risk assessments of station footpath crossings. Risk scores are allocated to unauthorised use, number of users, train numbers, non-stop train numbers, train speeds, lines crossed, warning times, weather conditions, track cant, other local factors – and the ‘probability of anyone stepping out from behind a train into the path of another’.

Scores are totalled up to a maximum of ‘86’. If a level crossing scores more than ‘55’, steps should be taken to reduce risks. If it scores between ‘35’ and ‘55’, risk reduction measures should be considered. Less than ‘35’, no action is required, apart from a periodic review to see if any circumstances have changed.

Assessment Sheets clearly state this scoring system.

But this entire method is a ‘stop-gap’. Network Rail and other rail industry bodies are developing a computer-based model to estimate the risk of death each year at every crossing. A form of this model has existed since 1995 for road level crossings – and the aim is to deploy this All Level Crossing Risk Model to assess risks at station footpath crossings, like Elsenham, by the end of 2006.

6. Safety responsibility

Network Rail, Train Operating Companies and highway authorities share responsibility for maximising level crossing safety.

By December 2005, a National Level Crossing Safety Group aims to improve the behaviour of crossing users. A steering body consists of Network Rail, the Rail Safety Standards Board, Association of Train Operating Companies, British Transport Police, Health & Safety Executive, County Surveyors’ Society and the Department for Transport. A working group adds the civil police and the Driving Standards Agency.

7. Rail safety campaign

In the Spring of 2005, Network Rail also cranks up its rail safety campaign, ‘No Messin’!’ Press releases are headlined: ‘Kids need to wrestle with their consciences’.

DJ Spoony of BBC Radio 1 launches the campaign, saying: “All kids want to have fun, but the railway isn’t a safe place to play…I’m more than happy to support a campaign that keeps young people safe and out of danger.”

Iain Coucher, then Network Rail’s deputy chief executive, adds: “Last year 34 people died on railway tracks…Each one represents a tragic story of ignoring all the warnings that the railway is not place to hang around, use as a short-cut or play on.”

8. Safety mandate

Level crossings are deemed to constitute the greatest risk to railway safety, with collisions at level crossings between vehicles and trains as the most feared potential catastrophe.

A fatally catastrophic collision underpins this fear in November 2004. A passenger train collides with a car stopped on the Ufton Nervet road crossing.

In 2005, a clear immediate priority for Network Rail is to restore public confidence in the safety of the UK’s railways. A cluster of catastrophic train crashes has shattered public confidence:

- Ufton Nervet (seven killed, 71 injured, November 2004)

- Potters Bar (seven killed, 76 injured, May 2002)

- Great Heck or Selby (10 killed, 82 injured, February 2001)

- Hatfield (four fatalities, 70 injured, October 2000)

- Ladbroke Grove (31 killed, 425 injured, October 1999)

- Southall (seven fatalities, 100 injured, September 1997).

A vehicle on the tracks causes Great Heck. Trains failing to stop at red lights are the immediate causes of Ladbroke Grove and Southall.

Potters Bar and Hatfield are unequivocally caused by fragmented, excessively complex, and dysfunctional relationships involved in track maintenance. These ‘interface’ relationships are a legacy of the privatisation of Britain’s railways in 1996-97, and of Railtrack, the wholly private, profit-seeking company that took over responsibility from British Rail for railway infrastructure in April 1994.

Hatfield is often described as a ‘watershed moment’ for the privatised rail industry. Four people are killed in a buffet car that crashes into a lineside mast. The roof is torn off and the carriage side gashed.

Network Rail replaced Railtrack as rail infrastructure owner and operator in October 2002. Of those rail disasters, only Ufton Nervet occurs in the new Network Rail era – and a November 2007 inquest returns a verdict that the Ufton Nervet crash was tragically caused by the car driver’s suicide.

Reacting to British public pressure over Railtrack’s failures in relation to making the railways efficient, the government in 2002 mandates Network Rail to ‘improve railway safety, reliability and efficiency’.

The potential threat posed by cars to trains at level crossings is deemed more significant than the threat of trains to pedestrians at level crossings. But the number of pedestrians killed at all types of level crossings exceeds that of road vehicle occupants and train passengers.

Between 1994-2005, 122 people have been accidentally killed at level crossings of all types.

Pedestrian fatalities number 84, road vehicle occupants 32, and six are on board train passengers.

Suicides and suspected suicides are not included.

Three of the 84 fatalities occur at footpath crossings with Miniature Warning Lights.

The figures also suggest older people – and not younger people –are at greater risk at such crossings.

9. April 2005 risk assessment

Network Rail staff carry out an April 2005 risk assessment at Elsenham station footpath crossing.

They score the crossing with a risk total of ‘28’ – meaning a level of estimated risk requiring no safety improvements.

PART 3: Happy and excited 1. Approaching trains 2. ‘Strike in’ 3. Emergency brake 4. Aftermath 5. Trauma 6. Fatalities 7. Heartbroken 8. Charlotte 9. Olivia

Happy and excited

1. Approaching trains

It’s now just after 10.30 on Saturday morning, 3 December 2005.

Local resident Alison Dinsdale drives to Elsenham and drops her son at the station. Dinsdale sees him cross to the Down platform.

At this time, Olivia and Charlotte are making their way along the Up platform.

The girls go inside the booking office. Booking clerk Kim Wilmott is helping a passenger to renew a season ticket. According to Wilmott, Olivia and Charlotte are ‘happy and excited’ and want to catch the 10.41 train to Cambridge. The passenger renewing the season ticket is not in a hurry and stands aside to let the girls buy their tickets.

Charlotte and Olivia consider whether to buy tickets to travel to Cambridge and then return to Bishop’s Stortford, a station two stops south of Elsenham. The clerk repeats this request.

Olivia and Charlotte confer again. The girls opt for Elsenham-Cambridge-Elsenham return tickets. Wilmott repeats this second request. The girls agree. The clerk prints their tickets.

Charlotte and Olivia then discuss payment. One of the girls decides to pay for both tickets. Wilmott hands the tickets to the girls, who then talk to each other about sorting out the money.

The booking office system records the sales of two half-price return tickets at 1039 hours.

About five minutes earlier – at 1035hrs – the bell had sounded to notify the road crossing keeper of the train’s approach. The keeper begins to close the vehicular crossing gates and interlock them with the signals.

The girls’ intended northbound Down line train is a Class 317 Electric Multiple Unit consisting of four cars, with a total length of 81 metres (88.6 yards).

Craig Swanick, a driver instructor, responsible for the train, supervises trainee driver John Rossiter-Summers. The train has an On Train Data Recorder. This Cambridge service is running on time.

A minute earlier – at 1034 – a second oncoming train, travelling south on the Up line leaves Audley End station, six miles north of Elsenham.

Geoffrey Waters drives the Class 158 Super Sprinter train.

The train is a two-car Diesel Multiple Unit – the lead unit numbered 158856 – with a total length of 44 metres. The unit also has an OTDR.

Central Trains, a National Express subsidiary, operate the train service, the 0724 hours from Birmingham New Street to Stansted Airport.

This service is running at least two minutes late.

Olivia and Charlotte are still in the booking office on the Up platform as these two trains start to approach Elsenham. The girls will need to cross back over the tracks if they want to catch the 1041 Cambridge-bound Down line train.

By 1037, the keeper has closed and locked the road crossing gates to traffic and thereby opened the railway to the approaching train. Alison Dinsdale in her car is now one of the motorists waiting behind the closed road gates.

The keeper removes the two keys from the road gate mechanism. He returns to his cabin and places the keys into the control panel. This clears the signals to allow the Cambridge-bound train to call at Elsenham – and the Stansted-bound fast train to pass through.

At this time, as always, the pedestrian wicket gates are unlocked. Pedestrians and intending passengers can still use the footpath crossing, even though the road gates are locked and the railway opened to trains.

Signalling detects the final approach of the Cambridge-bound train. At 10.39 and 24 seconds, the Cambridge train ‘strikes in’ 715m (782 yds) from the station.

This activates treadles on either side of the crossing. These activate the single tone yodel alarm, extinguish the green lights and illuminate the red warning lights just two-tenths of a second after the ‘strike in’.

But there is no additional distinctive indication to warn footpath crossing users of the approach of the second train, the Stansted service. No signs or voice messages warn of the possible approach of a second and non-stopping train.

Neither do any signs state only 20 seconds could elapse between the activation of the warning lights and alarm and the arrival of an approaching train.

2. ‘Strike in’

The yodel alarm can now be heard. One of the girls asks the clerk if the alarm is for their Cambridge train. The clerk advises Olivia and Charlotte to check with the level crossing keeper. Wilmott hears one of the girls say: “I hope we don’t miss this train.”

The yodel alarm heard by the girls is for their Cambridge train, the 0950 hours London Liverpool Street to Cambridge service.

Charlotte and Olivia leave the booking office, go down the short ramp and reach the crossing gate at the north end of the Up platform.

10:39:51. Waters sounds the express train’s horn at the whistle board just north of Elsenham. The horn sounds almost at the same time as his train also ‘strikes in’.

The second train’s ‘strike in’ would have activated the warning lights and alarm at the footpath station crossing – but only if Waters’ express train had been the only approaching train. The Cambridge-bound train has already ‘struck in’ – and activated the lights and alarm 28.4 seconds earlier.

Even at this point, with both trains less than 30 seconds away from the station, pedestrians and intending passengers can still open the footpath crossing wicket gates and try to cross the railway.

Trainee driver John Rossiter-Summers hears the horn of the express about 400 yards ahead of him on the southbound track but the express train is still out of sight beyond the curve.

At this time, Waters in the express train cannot not see Elsenham station – and crossing users on the Up platform side are still unable to see the train and are possibly unaware of its approach if they have not heard its horn.

Rossiter-Summers slows his Cambridge train to about 30mph (48km/h) as it nears the crossing. The front end of the Cambridge train arrives at the crossing – 38.2 seconds after its ‘strike-in’. It will take 12.1 seconds for his train to clear the crossing.

Rossiter-Summers sees the girls standing at the non-locking pedestrian gate. One of the girls has her hand on the gate and opens it.

The other girl is seen running the short distance from the booking office to the gate. She is behind her friend when the front of the Cambridge train actually passes over the crossing.

“I made eye contact and shook my head, and mouthed, ‘I’ll wait’,” says Rossiter-Summers.

Witnesses say Olivia and Charlotte hold the Up gate open and wait whilst their Cambridge train passes over the crossing. They wait between the gate posts, at a point between the gate and the track.

The waiting girls are said to appear happy and excited – but not agitated.

3. Emergency brake

Olivia and Charlotte might now be thinking that the ongoing red light and single-tone alarm relate only to their Cambridge train. They watch as the train passes over the crossing and slows to stop at the Down platform.

Rossiter-Summers decelerates his train further to about 15mph (24km/h). The second coach of his four-car train is in the Down platform. Rossiter-Summers now sees the Stansted train approaching Elsenham on the opposite line.

10.40 – and 14 seconds: The southbound fast train, now on the curved Up line approach to Elsenham, is travelling at over 65mph.

The rear coach of the girls’ Down train passes over the crossing. The Cambridge train begins to slow to a halt at the platform. Moments before it comes to a stop, the Stansted train passes the Cambridge train.

The red lights remain lit and the yodel alarm still sounds.

“The express was past me, not even in a second,” says Rossiter-Summers, afterwards. “It was travelling so quick.”

Motorist Alison Dinsdale sees Olivia and Charlotte arm-in-arm. The crossing keeper also sees the girls go through the open gate.

Dinsdale sees them make a “dash for it”; for their Cambridge train now slowing in the Down platform diagonally ahead of the crossing.

Ian Potter is also there. “The red light was on,” says Potter. “The first girl opened the gate to go through and the second girl was one step behind her.

“They were trying to catch the train. I remember thinking they weren’t going to make it.”

The girls are now in the path of the second train.

Waters, driving the second train coming, first sees the Cambridge-bound train at the opposite Down platform. As the Stansted train rounds the left hand curve on the Up line, he sees cars waiting behind the road crossing gates.

Waters then sees two people on the crossing in front of his train, one behind the other.

“These two figures came out of nowhere,” recalls Waters. “They were right in the way on the track. They just ran straight in front of us.”

At 10.40 – and 15 seconds: “I put the emergency brake on,” says Waters. “I couldn’t stop.”

Waters applies a full emergency brake with the train speed recorded at 65.3mph (104.6km/h). The train approaches Elsenham crossing at a speed where 29 metres (32 yards) is travelled every second.

Even with the emergency brake applied, the train cannot stop. It clears the crossing in 1.8 seconds.

Less than half a second later, the miniature warning light returns to green.

The yodel alarm is silenced.

**

4. Aftermath

Waters makes an emergency call on the train radio.

Waters suspects his Stansted train has hit two people. He speaks to a Network Rail signaller at Liverpool Street and asks for all train traffic to stop. He tells the senior conductor on his Stansted train about the incident.

Waters draws his train forwards a short distance to the next signal with a signal post telephone. The driver descends to the track and heads for the phone.

Waters sees clear signs of an accident.

He gives details of the accident to a Liverpool Street IECC signaller. The recording of this conversation suffers from a fault in the voice recording machine.

The crossing keeper returns to his cabin. He removes the gate keys from the control panel. This means the signals are at red and no further trains can pass.

Rossiter-Summers and his instructor are aware that something has happened on the other line behind them.

He completes his usual departure checks. Their train leaves for Cambridge – without Olivia and Charlotte.

Witness Ian Potter, who saw Olivia and Charlotte in the moments leading up to the accident, says: “They were just a couple of girls, laughing and joking.

“They didn’t seem to have a care in the world.”

**

5. Trauma

Witnesses and the train drivers – both Waters and Rossiter-Summers – suffer considerable trauma. As the Stansted train passed, Cambridge train driver Rossiter-Summers was occupied with releasing the doors and watching passengers getting on and off his train.

However, instructor Craig Swanick had lowered the window on the right side of the driving cab and looked back toward the crossing. The instructor thought the girls were in the ‘four foot’, the recess between the tracks and the platform edge – and that they were waiting for his train to pass.

This ‘momentary vision’ ended when the Stansted train passed and blocked his view. He then saw people running on the platform and heard shouting.

Rossiter-Summers and his instructor hear about the accident when they arrive at Cambridge. Both are upset and are allowed to go home.

Police, ambulance and fire service personnel are on site within minutes. A Rail Incident Officer arrives at Elsenham at 1120hrs. Police protect evidence by establishing a cordon around the site.

A British Transport Police officer accompanies the Stansted train driver. Another BTP officer boards the train to speak to its passengers.

A relief driver for the Stansted train arrives at 1235. Waters and the train conductor are taken home in a taxi 15 minutes later.

British Transport Police hand the site of the tragedy back to Network Rail at 1351. The Stansted train continues its journey at 1355.

Undertakers are expected at 1330.

A Network Rail contractor completes work by 1445. Normal line working is resumed.

Crossing keeper Joe Carriman is offered the chance to be relieved of his duties soon after the tragedy. Carriman is offered counselling but prefers to continue working and complete his shift.

Signalling engineers temporarily lock the footpath wicket gates out of use, ‘pending tests on the integrity of the crossing equipment’.

6. Fatalities

Timings later provided suggest Olivia Bazlinton and Charlotte Thompson stepped onto the crossing at the very second the alarms would have ceased as the Cambridge-bound train they intended to catch cleared the crossing. The implication is they did not realise a second train was approaching the crossing.

Charlotte and Olivia are the 123rd and 124th accidental deaths at level crossings in the UK since 1994. (This excludes suicides and suspected suicides).

Charlotte and Olivia are the 85th and 86th pedestrians to die accidentally at a level crossing and the fourth and fifth to die at footpath crossings fitted with Miniature Warning Lights.

The girls are the first people since 1994 to be killed at a station footpath crossing fitted with MWLs.

Their deaths are the first fatalities at Elsenham station since 20 November 1989 – when a train killed a 69-year-old woman, an intending passenger, on the footpath crossing.

7. Heartbroken

A north London vicar regularly preaches that an average person living in Britain can expect to live for ‘three score and ten’, or 70 years.

“Maybe, it’s better to think of this as 25,550 days,” says the vicar.

Applying this, it means Olivia Bazlinton and Charlotte Thompson have lived just over 5,110 and 4,745 days respectively.

The families of Olivia and Charlotte are devastated.

Two balloons tied to the school railings, one pink and one scarlet, nudge each other in the breeze outside Newport Free Grammar School. Headteacher Richard Priestly offers pupils counselling after the tragedy. A deeply shocked Priestly says of the two girls: “They were full of life and had everything ahead of them.”

8. Charlotte

Mourners lay flowers, messages of remembrance and cuddly toys at Elsenham station over the next few days. Charlotte’s older brother, Robbie, 15, plays on his guitar, Time of Your Life, a song by the rock group Green Day, as he leads a spontaneous tribute to his sister Charlie outside Elsenham station.

Charlotte’s former Brownie leader Jennifer Jarvis says Charlotte was a “lovely girl” and “everyone warmed to her”.

Reg and Hilary Thompson, Charlotte’s parents, who live in nearby Thaxted, pay tribute to their “beautiful, vivacious and generous girl”.

A family statement says: ‘A fog of emptiness descended upon us. Our thoughts are with Olivia’s family – and the families of all those children who for no reason that we can think of are taken from us before their time.

‘We know that all around the world people suffer appalling misery every day. We are not singled out. Charlie will never leave us and we will never leave her. In her short life she brought happiness to so many. She was an angel.’

Hilary says: “You take the next breath because you have to. We are all lost without her. Charlie was the engine of the family…We live for our children…They are our life.”

9. Olivia

Olivia’s sister Stephanie leaves a tribute at the scene of the tragedy: ‘RIP Olivia and Charlotte xxx. You will always be loved and never forgotten. Always in our hearts xxx Your heartbroken big sis.’

PART 4: Grief and anger 1. ‘Bear trap’ 2. Locks 3. 5th December re-assessment 4. ‘Safe, if used correctly 5. 1989 fatality 6. Occurrences 7. ‘Misuse’ 8. Gut instinct 9. Services 10. Further incidents 11. The Weir photograph

Grief and anger

1. ‘Bear trap’

Grief mixes with anger.

Reg Thompson labels Elsenham station’s pedestrian level crossing as a “bear trap in the woods”.

Thompson explains the girls were not trespassing, playing or hanging around on the railway. They were intending passengers with purchased tickets, using one of Network Rail’s risk assessed station footpath level crossings.

The families also criticise the absence of ticket machines on the Down platform. Cambridge-bound passengers, like Olivia and Charlotte, could have avoided the need to cross the tracks if the Down platform had a ticket machine and/or a ‘permit to travel’ machine.

A ‘one’ Railway Group Station Manager is responsible for ten stations, including Elsenham. She says the other nine stations similarly have sales facilities on just one platform. But footbridges connect platforms at every station – except Elsenham.

Chris Bazlinton, Olivia’s father, strongly echoes Thompson. “Of course, the girls made a mistake. They’re still only children. Olivia is not the only one who has attempted to cross the tracks with the pedestrian signals still at red – commuters can be seen running across most days,” says Bazlinton.

He remains adamant Olivia and Charlotte would still be alive if the pedestrian gates had locked – either manually or automatically in tandem with train signals that indicate an approaching train. “If the pedestrian gate had been locked Olivia and Charlotte would not have crossed. They’d have laughed it off, and waited for the next Cambridge train,” says Bazlinton.

Other people tell Bazlinton in the days and weeks after the tragedy they too have crossed the tracks when the red light shows. “You can push the gate open at any time,” he says.

Olivia’s father is also sure the girls would still be alive if the level crossing had been equipped with a second, differently sounding alarm that would have enabled the girls to distinguish between their 1041 train halting at the Down platform and that second rapidly approaching fast train. “If a second, different sound had gone off, I know again, they wouldn’t have crossed,” says Bazlinton.

Similarly, he feels the girls would not have stepped onto the crossing if a spoken message about the ‘second train coming’ had sounded.

Reg Thompson recalls claims by Network Rail, made in the aftermath of the tragedy, that the girls had acted recklessly and that somehow their youthful exuberance had led to their deaths.

“I never believed that Charlie and Liv were the architects of their own terrible end,” says Thompson later.

Three thousand people sign a petition in the Herts & Essex Observer demanding Network Rail fit locking pedestrian gates.

2. Locks

“The deaths of Charlotte and Olivia were a tragedy, and will never be forgotten,” says Jon Wiseman, Network Rail’s Anglia route director.

In the aftermath of the December 2005 tragedy, national media reporters and specialist railway journalists focus on whether locking gates could have prevented the deaths of Olivia and Charlotte.

Network Rail insists locking gates might trap people on the tracks between the gates.

Chris Randall, editor of Rail Professional magazine, writing in May 2006, disagrees and responds: ‘There is a recess (next to the tracks) at Elsenham where anyone in danger can take refuge.’

Randall, a seasoned rail industry observer, adds: ‘A simple lock, operated either manually or automatically when a train is approaching, would have almost certainly prevented the deaths of Olivia and Charlotte.’

The widespread expectation after the December 2005 tragedy is for Network Rail – as crossing provider – to take prompt commonsense action to make Elsenham’s pedestrian level crossing safer for crossing users.

Train drivers report three near misses involving pedestrians that were logged by Network Rail. But the drivers claim no action was taken.

Crossing keeper Joe Carriman tells British Transport Police: “I don’t know what the bosses will do. I think they should lock the pedestrian gates as they did the main (road) gates.”

Central Trains subject their lead Stansted unit 158856 to an independently verified technical investigation. The unit’s braking performance meets the required standard.

3. 5 December re-assessment

On 5 December, two days after the deaths of Olivia and Charlotte – and as national media cover the tragedy – Network Rail re-assesses risks at the station and acknowledges that Elsenham has the third highest risks at any station pedestrian crossing in the United Kingdom.

The April 2005 assessment had accorded Elsenham a risk score of 28 – meaning a level of risk requiring no safety improvements. But the 5 December re-assessment scores Elsenham at ‘47’, meaning extra safety measures should be considered in accordance with rail industry standard G1/RT7011. Only footpath crossings at Crowle (48) and Downham Market (53) score higher.

A glaring disparity now arises between the April assessment score of ‘28’ and the December re-assessment tally of ‘47’. The station pedestrian crossing has not changed during the period between the two assessments.

Later, it transpires the differences arise due to incorrect scores for ‘frequency of misuse’, ‘frequency of use’, ‘number of trains’, and ‘probability of stepping out from behind a train’.

The main difference is said to arise because the crossing keeper questioned in April did not inform the risk assessor about the frequency of misuse. This frequency could have been established from the daily log of events – if the instances of ‘misuse’ noted in the keeper’s Occurrence Book had also been reported to the controlling signaller.

The daily log would also have allowed ‘misuse’ instances to be included in the railway industry’s national Safety Management Information System database. SMIS data can trigger safety reviews.

The re-assessment of Elsenham shows specific factors may increase ‘misuse’, including an intending passenger’s wish to catch a particular train, and, the requirement of Cambridge-bound passengers to buy a ticket from the booking office or from one of the machines located only on the Up platform.

Cambridge-bound passengers travelling without a ticket are also likely to incur a penalty fare – so they must cross to the Up platform to buy a ticket and then cross back over the tracks to catch their train.

4. ‘Safe, if used correctly’

However, it is now acknowledged after the tragedy that the semi-quantitative risk assessment scoring method is not sufficiently sophisticated to record such ‘local factors’. Only the awareness and skill of each risk assessor can identify and take these factors into account.

Accident investigators describe the risk assessment scoring system as ‘not a sophisticated tool’. Certain assessment criteria depend on ‘the judgment of the assessor’.

Investigators also find the quantitative risk assessment method is ‘a temporary solution…prior to the development of a more sophisticated quantified tool, the All Level Crossing Risk Model (ALCRM). Work on this model is currently in progress’.

This implies Olivia and Charlotte have used a level crossing where risk is assessed by an unsophisticated and stop-gap method – whilst a newer, more refined model is still being developed.

But, despite growing recognition of emerging flaws in Network Rail’s risk assessments of Elsenham, the company publicly persists with a mantra that the Elsenham crossing is safe, if used correctly.

This stance is seen as clearly implying the girls are to blame for failing to abide strictly by ongoing crossing warning lights and the alarm.

Network Rail also says installing a footbridge would be unjustified and too expensive.

5. 1989 fatality

The deaths of Olivia Bazlinton and Charlotte Thompson are the first fatalities at Elsenham station since a train killed a 69-year-old woman, an intending passenger, on the footpath crossing on 20 November 1989.

The woman had stepped out behind a stopping train. She had tried to use the footpath crossing from the Down side towards the Up side. She crossed while the MWL showed red, possibly believing the red light related to the stopping Down train that had passed over the crossing – and not to the possibility of a second train coming on the Up line. A coroner’s verdict was accidental death.

The local parish council expressed concern about the position and visibility of the warning lights – and the warning time given of approaching trains. British Rail, then in control of the UK’s rail infrastructure, measured train speeds, warning times and observed the crossing’s operation. BR said the warning lights and times conformed to Her Majesty’s Railway Inspectorate’s requirements.

HMRI inspected Elsenham level crossing in February 1990 and decided to make minor changes to the footpath crossing’s layout, to reposition the MWLs and remove redundant warning signs. Nobody suggested locking the wicket gates.

It was decided to fit an audible yodel alarm to supplement the red light warning.

HMRI and BR also agreed a second tone alarm should be installed so that ‘the second train situation should be reflected by a hurry nature in the tone of the alarm’. All of the modified recommendations were implemented during 1990 – except the second tone audible alarm to warn of a second approaching train.

Between 1990 and 2005, the crossing remained unchanged.

6. Occurrences

In the weeks and months after the December 2005 tragedy, anecdotes emerge that crossing users of all ages have – since 1989 – frequently crossed the line when the red light shows and the yodel sounds.

Crossing keepers maintain Occurrence Books kept in the keeper’s cabin. Many entries relate to public ‘misuse’ of the crossing. One keeper makes few entries. Another makes occasional entries whilst a third makes numerous.

All keepers make entries about individuals crossing against the red MWLs. Many relate to teenagers’ behaviour on the crossing and around the station. Frequent comments are made about teenagers travelling without a ticket.

Eleven ‘Occurrence’ Books’, analysed after December 2005, record 303 such ‘misuse’ instances between 10 April 1999 and 6 December 2005 – the latter three days after Olivia and Charlotte are killed. Of these, 140 involve adult men, 44 adult women, 61 boys and 26 girls. The rest involve mixed groups or the gender is not identified. More than 90% are people who start to cross after the lights turn red.

Accident investigators believe the actual occurrence of ‘misuse’ of the station footpath crossing is even higher than the books show.

7. ‘Misuse’

The term ‘misuse’, in the context of level crossings, is used by the railway industry to cover both intentional and unintentional use of a crossing, particularly when visual and audible warnings indicate it is not safe to cross the lines. Unfortunately, the term creates confusion and breeds complacency about the risk posed by certain level crossings, such as Elsenham,

Worryingly, many people continue to either unintentionally or deliberately misuse the Elsenham crossing after December 2005 and well into 2006.

Forced to use the road crossing whilst the footpath crossing gates are temporarily locked ‘pending investigations’, some pedestrian users are observed impatiently climbing over the closed road gates to reach the opposite platform. They do so despite verbal warnings from Network Rail staff and irrespective of floral tributes in memory of Charlotte and Olivia.

Three instances of ‘misuse’ are recorded during a 20-day period after the accident when the crossing is under scrutiny, including a period of video surveillance.

8. Gut instinct

Just a few days after the December 2005 tragedy, Christian Wolmar, one of Britain’s leading transport commentators and historians, visits Elsenham and writes: ‘The whole feel of the crossing was something out of the Railway Children film, perfectly suitable for a branch line with a few trains per day, but not for a busy line with up to eight trains an hour including freight.’

Wolmar accepts each risk has to be scored scientifically and expressed mathematically. But he adds: ‘There is, too, a role for gut instinct and that is sometimes lost in the fug of rules, procedures and regulation that now govern everything on the railway.

‘Just one glance at the crossing with its badly painted wobbly line on the tracks and the cute little latch-less wicket gate, which offers no hint of the dangers posed by the location, should be enough to make any concerned railway manager gasp in disbelief…The principle of making risk ‘as low as reasonably possible’ seems not to have been applied sensibly here.

‘I suspect there will be major changes at Elsenham, too late for the two girls.’

9. Services

A special memorial thanksgiving service celebrates the lives of Olivia and Charlotte. Hundreds of people gather for the service at St Mary the Virgin church at Newport on 19 December 2005. A cremation service for Olivia takes place afterwards.

Olivia Bazlinton’s funeral takes place on year later at St Mary’s Church, Newport, on 24 February 2007.

‘So many smiles, So much laughter, So much fun, So much love,’ reads an inscription.

10. Further incidents

Four months after the tragedy, the author visits Elsenham on a cold Tuesday evening in March. Writing for Rail Professional magazine in May 2006, the author observes further incidents:

‘I hadn’t been there long when I saw an elderly woman crossing whilst the warning light was showing red,’ writes Paul Coleman. ‘She tugged in vain at the hinge end of the wicket gate. The gate has no handle to pull, so it’s an easy mistake, particularly at night for someone partially sighted. After a few seconds, she turned and managed to open the gate before hobbling slightly across the tracks. The train came through about 50 seconds later.

‘Risk-taker number two was a middle-aged commuter, booted-and-suited with briefcase. He cut it finer, opening the unlocked gate and crossing whilst the red light was on and the warning alarm was sounding. The train came through about 30 seconds afterwards.

‘Later, a down line train arrived and stood at the platform. A second up line train was also approaching but there was nothing distinctive to signal that the latter train was approaching. The driver sounded his horn. Drivers had expressed worries about Elsenham before.

‘It is understood that a train driver who lives in Elsenham has written to the route manager (at Network Rail) to install whistle boards that would tell drivers to sound their horns. Now, it seems drivers ignore residents’ noise concerns and routinely sound their horns.

‘Half-an-hour later, the road barriers were closed once more. The red light glowed in the gloom and the alarm was sounding. A teenage boy standing on the village side of the tracks, clutching a football, opened the gate and stood close to the cess rail, glancing up and down the tracks. His mates, standing on the Up platform, called to him. One of them, a can of Special Brew (strong lager) in his hand, then tried to dissuade him from crossing.

‘The lad with the ball stared for a few seconds back along the downline. He leant forward, almost over the cess rail (the rail closest to the recess area beside the tracks). He stepped back through the wicket gate and waited for a Down train to pass. Instead, an Up London-bound train raced through. More by luck than judgment, ‘there but for the grace, went he.’

11.The Weir photograph

Photographer Simon Weir, on another day in Spring 2006, then photographs two boys racing across the tracks after the audible alarm sounds (see photo above). Drivers watch the boys from their cars that queue safely behind vehicle gates closed several minutes earlier by the crossing keeper.

Between the tragedy and May 2006, journalists and rail officials reportedly witness at least six incidents of people crossing when trains are approaching.

In June 2006, a 12-year-old boy reportedly gets off one train and is almost struck by a second train coming as he runs over the crossing.

Of Network Rail’s failure to take basic remedial safety measures in the aftermath of the December 2005 fatalities, Chris Randall of Rail Professional adds, prophetically: ‘Network Rail’s failure to take even the most basic and obvious steps to prevent another Elsenham is at best incompetence, at worst complacency – and Network Rail should not be surprised if, once investigations have been completed, it finds itself facing formal accusations of negligence.’

PART 5: Network Rail – the company 1. Families and Network Rail 2. ‘Hybrid’ organisation 3. Fragmentation 4. Hatfield and Potters Bar 5. Accountability and Transparency 6. Finance 7. John Armitt

Network Rail – the company

1. Families and Network Rail

The families of Olivia Bazlinton and Charlotte Thompson now encounter Network Rail.

Several individuals who represent the company, including executive members of the board of directors and West Anglia route managers and staff, meet face-to-face with the girls’ parents.