Ballots and Dogma

By Paul Coleman

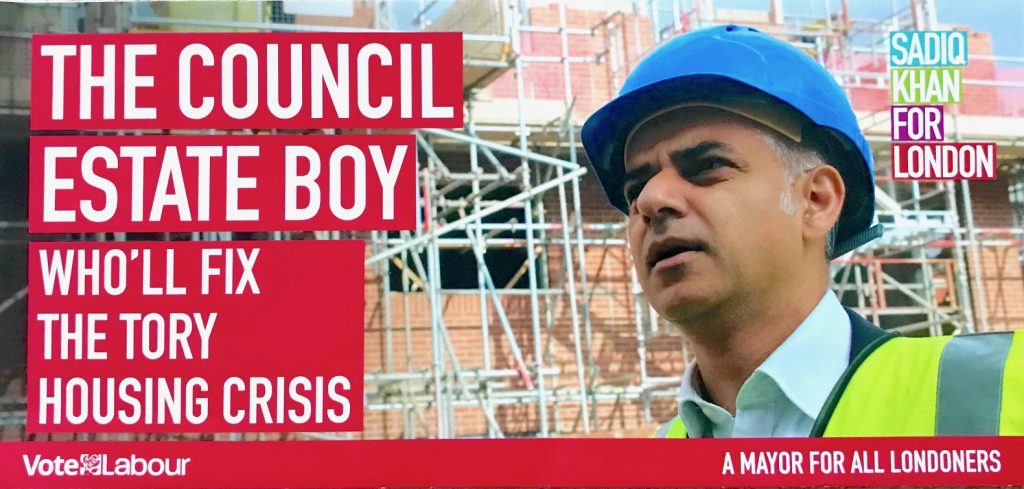

London Mayor Sadiq Khan repeatedly tells Londoners he is ‘the council estate boy who’ll fix the Tory housing crisis’.

Londoners elect Khan in May 2016. Khan is Londoners’ third mayor since they pushed New Labour to create London’s mayoralty in 2000.

Two years pass during which Khan, a New Labour social democrat from the Blair-Brown era, constantly condemns a national Conservative government’s austerity policies for worsening London’s housing crisis. But Khan ignores how council estate ‘regeneration’ schemes, dogmatically pursued by several Labour-led councils, catastrophically impact on thousands of working class Londoners.

Social cleansing & regeneration

Resident campaigners blame Labour-run councils, like Haringey, Southwark, Newham and Lambeth, for routinely allowing property developers and mutant corporate housing associations to demolish dozens of council estates across London. Thousands of secure council tenants and Right to Buy leaseholders across London are displaced and dispersed by developers acting in tandem with collaborative Labour-led councils.

Many Londoners view Labour councils as no better than Conservative-controlled boroughs like Barnet, Kensington and Chelsea, and Westminster, precisely because they dogmatically pursue this ‘social cleansing’ guised as ‘regeneration’.

Such developer-driven ‘regeneration’ causes chronic net losses of council homes. Such homes are desperately needed by Londoners. For instance, 1,212 south London council homes are permanently lost when developer Lendlease and Southwark Council demolish the Heygate Estate in Walworth.

Estate ‘regeneration’ also produces massive net gains of private market homes. The vast majority of Londoners – struggling on stagnant incomes since the financial meltdown of 2008-09 – simply cannot afford to buy or even rent these new units.

Grahame Park

Labour-led councils claim Tory central government austerity leaves them with no choice but to become more ‘entrepreneurial’ in relation to ‘regeneration’. They say they need Mayor Khan to agree to release public funds – held by the Greater London Authority – to grease the rails for such ‘regeneration’ schemes.

Khan withholds funds only for a limited number of such schemes, such as for the demolition and redevelopment of Grahame Park, an estate ‘regeneration’ endorsed by Tory-run Barnet. Khan says a Genesis housing association scheme fails to provide enough ‘affordable homes’.

However, Khan endorses GLA funds for a welter of council estate ‘regeneration’ schemes. In doing so, they say Labour Mayor Khan functions just like his Conservative mayoral predecessor, Alexander de Pfeffel Boris Johnson, London’s second mayor.

The demolition-led ‘regeneration’ of council estates and their replacement by unaffordable private housing boomed under Johnson’s mayoralty (2008-16). Khan’s mayoralty continues to extend such schemes and further distress, displace and disperse working class Londoners who live on these estates.

Pressure

Hence, under Khan as under Johnson, a worsening housing crisis for the many also represents a housing boom for a few. Despite Khan’s ‘council house boy’ rhetoric, Londoners struggle whilst real estate and ‘regeneration’ industry players thrive.

Mayor Khan is also reluctant to introduce ballots for council estate tenants and leaseholders. Resident campaigners argue it is only right and democratic that council estate residents should be allowed ballots on whether their homes are demolished or not.

They say residents should be able to wield democratic control via such ballots to influence and even veto ‘regeneration’ schemes that seek GLA public subsidy. Khan comes under increasing pressure from housing campaigners to redress this democratic deficit.

Power to influence

Rewind to the summer of 2016. Britain votes to leave the European Union. Brazil hosts the Olympic Games. Iceland dump England out of the European Football Championships.

Sadiq Khan takes office as the newly elected Mayor of London. The Mayoralty gives the self-styled ‘council house boy’ considerable power to tackle London’s chronic shortage of genuinely affordable homes for Londoners.

Mayor Khan says he seeks to “double the current rate of housebuilding” and demands “half of new homes be genuinely affordable”. Khan controls a £4.8 billion programme to stimulate the building of 116,000 ‘affordable’ homes by 2022.

Hence, Khan could strongly influence local authorities on planning policies. He could pressure housing associations, developers and housebuilders to build more council and social housing for Londoners. He could compel private landlords to improve their offer to tenants.

Khan could also give council estate residents a real voice and a decisive vote on whether their homes are demolished and on how those homes are to be replaced. But it’s not until the summer of 2018 that Khan, a former council estate resident, finally gives residents on some London estates a right to a ballot on whether councils, developers and housing associations can demolish and redevelop their homes under the guise of ‘regeneration’.

Conditional

Many London council estate ‘regeneration’ projects are pushed through against the wishes of their residents in the two years prior to Khan’s introduction of ballots. Nevertheless, Khan is the first politician to insist that state funding for estate ‘regeneration’ schemes – GLA funds, in this instance – is now conditional on a residents’ ballot.

Existing national law does not require council tenants to be balloted about the demolition and redevelopment of their homes. Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn endorses estate residents’ ballots during his 2017 party conference speech to delegates – but it remains unclear if residents’ ballots are officially Labour Party policy.

Finally, in July 2018, two years after his election, Mayor Khan decrees any landlord, developer, housing association, council or partnership – seeking GLA funds for a ‘strategic’ council estate ‘regeneration’ project – must show they have secured residents’ support through a ballot.

Khan says he wants to make sure the ‘regeneration’ of London’s council housing estates “happens with residents’ support and engagement”. “This is to make sure that GLA funding only supports estate regeneration projects if residents have had a clear say in plans and support them going ahead,” says Khan.

Cut-off

‘The Mayor expects a resident ballot to be a milestone in an estate regeneration process,’ states the GLA’s Capital Funding Guide. ‘It should be the culmination of a period of resident consultation, engagement and negotiation; it should not, however, be the end of the process of engaging with residents.’

Ballots must be held if a scheme seeking GLA funding plans to demolish social or council homes and to replace them with 150 or more homes of any tenure. A required ballot is ‘triggered’ even if demolished homes are owned and sold through Right to Buy.

Khan’s Mayoral office publishes a list of council estates regeneration projects ‘known to be named in a secured and signed funding contract with the GLA as of 18 July 2018’. That cut-off date proves important.

Many councils, developers and housing associations promoting regeneration schemes are already seeking GLA funding. They may apply to the GLA for a ‘transitional exemption’ from the need to ballot residents if their scheme has ‘secured outline or full planning permission on or prior to 18 July 2018’.

The GLA says projects on its list may be subject to a ballot unless they seek such an exemption or the project falls beyond the scope of the ballots funding conditions.

Landlord Offer

Councils, developers and housing associations seeking GLA estate regeneration funds must make a ‘Landlord Offer’ to residents. This must detail ‘the broad vision, priorities and objectives of the project, including the estimated number of new homes and the mix of tenures’.

The Landlord Offer must set out the terms of a ‘full right to return or remain for social tenants’ who want to return to live in a new home on the redeveloped estate. The Offer must also set out terms and conditions to compensate Right to Buy leaseholders and also any freeholders.

Finally, the Landlord Offer must set out ‘commitments to ongoing consultation and engagement’.

Eligible

So who can vote? Mayor Khan says ballots must be open to all residents aged 16 years or older living in an existing council or social housing estate. These residents must though be social tenants with secure, assured, flexible or introductory tenancies.

They must be a named tenant on a tenancy agreement, dated on or before the date the Landlord Offer document is published. Resident leaseholders or freeholders can vote if they have lived in their properties as their only or principle home for at least one year prior to the Landlord Offer’s publication – and are named as the leaseholder or freeholder on the title for their property.

Other residents, irrespective of their tenure, can vote in a ballot if their principal home is on the estate and they have been on the local housing register for at least one year prior to the Landlord Offer.

Residents living in temporary accommodation and tenants renting from a private landlord are not eligible to vote – unless, once again, they have been on the local authority’s housing waiting list for at least one year before the Landlord Offer is made public.

The estate residents’ ballot is ‘one vote per person’ but there is no limit on the number of voters per household.

Right to return

Mayor Khan and the GLA say councils, developers and housing associations must appoint an ‘independent body with appropriate knowledge and expertise to undertake the ballot’. This body should ‘review the process for the registration of voters’.

A ballot should take place – ‘generally’ – before a council or a housing association appoints a developer as ‘partner’ to redevelop an estate and before any design of a redevelop estate is finalised. However, for some estate ‘regeneration’ schemes this is not the case.

The ballot should also be held before a council or housing association relocates residents for the purpose of redeveloping the estate – and before planning permission for the ‘regeneration’ project is obtained. However, eligible relocated residents are entitled to vote if they have a ‘right to return’ to a new home on the redeveloped site.

The GLA can also ask for its money back if a project deviates from the Landlord Offer.

Exemptions

Developers, councils and housing associations can apply for their demolition ‘regeneration’ scheme to be exempt from a residents’ ballot. Exemptions apply to schemes that support major infrastructure projects backed by law, such as Crossrail or High Speed 2, or to schemes that are designed to address worries about residents’ safety.

An estate regeneration project will also be exempt from a ballot if it re-provides supported and/or specialist housing, say for elderly people, on an existing estate exclusively made up of this type of housing.

However, the GLA can impose a ballot requirement if a council, developer or housing association changes an estate regeneration scheme in order to demolish more council homes or social housing – even if that scheme already has planning permission and/or secured GLA funding.

Belatedly and reluctant

The actual ‘Resident Ballot Requirement Funding Condition’ is inserted into documents published by the Mayor of London and the Greater London Authority.

But why did Sadiq Khan – blessed with the power of the Mayoralty – only belatedly introduce ballots? What does Mayor Khan’s dithering and reluctance say about the way these ballots might be held during 2019?

The promised ballot of Love Lane Estate residents in Tottenham will go a long way to answering these questions.

Sources:

Knock it Down or Do it Up: The challenge of estate regeneration, London Assembly Housing Committee, Greater London Authority, Feburary 2015

‘Resident Ballots for Estate Regeneration Projects,’ Section Eight, GLA Capital Funding Guide, Greater London Authority, 2018.

Other stories : The ‘council estate boy’ and his very British ballots https://www.londonintelligence.co.uk/a-very-british-ballot/

© Paul Coleman, London Intelligence, 2019

London Intelligence ® is a registered trademark of London Intelligence Limited.