MARKET FORCES: developer quits Tottenham Wards Corner regeneration

Tottenham Latin Village – Pueblito Paisa traders are ‘ecstatic’. Council pledges to work with traders and residents.

By Paul Coleman

(Photography: Courtesy of, and copyright of David Tothill ©)

Corporate property developers rarely withdraw from potentially lucrative London ‘regeneration’ schemes.

But, on Friday afternoon, 6 August 2021, Grainger announced its withdrawal from its Wards Corner regeneration scheme in south Tottenham.

Grainger, the UK’s ‘largest’ private residential landlord, had coveted Wards Corner at Seven Sisters for twenty years. In a post-mortem-type statement, Grainger explained: ‘After nearly two decades, Grainger has taken the difficult decision not to proceed with the Seven Sisters Regeneration project due to the rising cost to deliver the scheme.’

Risk

During that twenty years Grainger bore the corporate risk of trying to achieve at least a 20% profit on the Gross Development Value* of its Wards Corner scheme. Grainger claimed to have spent £10.7 million on pursuing its scheme by 2017, much on professional fees and buying out leases.

But, over that same period, a significant number of Wards Corner’s market traders, retailers and residents spent their own money, time and energy trying to stop the scheme. They believed the developer-driven, Council-backed scheme would destroy their families’ livelihoods and homes.

Women supporting families run many of the businesses. The businesses also support dozens of jobs.

Many have said Grainger’s scheme, backed by Haringey Council, has blighted their businesses and cramped the lives of their children. Traders have also had to keep running their businesses in a building they say has been neglected by its owner, Transport for London.

The Wards Corner Community Coalition of traders and residents are especially happy to see Grainger withdraw. They posted on social media: ‘Party time!’

Vicky Alvarez, originally from Colombia, is a market trader and chair of the Seven Sisters Market Traders Association. “For too long, market tenants and local residents have endured the deliberate neglect of the Market and Wards Corner while fearing their displacement by a scheme which puts profits before people,” says Alvarez.

Ecstatic

Wards Corner is not just a south Tottenham matter. The indoor market and Pueblito Paisa restaurant at Wards Corner attracts many Londoners from outside the area, including people who also originate from Latin America.

The indoor market has become known as the Latin Village. Many traders originate from Colombia. But other traders have also come from Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Honduras, El Salvador, Chile, and Venezuela. Some hail from Guyana, Iran, Uganda, Nigeria, Jamaica, Portugal and from other parts of Africa, Asia, and the West Indies.

Businesses owned by Indian, Turkish, and Cypriot traders are wrapped around other street-facing parts of Wards Corner on Tottenham High Road, West Green Road and Seven Sisters Road. The site also includes many residents who live in Victorian homes on Suffield Road.

“The announcement of Grainger’s withdrawal from Wards Corner will be widely welcomed by Latin American people in London,” adds Javiera Huxley, co-chair of Save Latin Village. “This is a huge victory in the fight for a fairer city. We are ecstatic.”

Welcome

Grainger’s withdrawal means the independent market traders can now try to secure the immediate future of their businesses – a mix of food and clothing stores, hair and beauty salons, money transfer shops, internet cafés, and barbershops. Wards Corner traders and residents will now hope to do the same for their shops and homes.

“Grainger’s withdrawal finally ends a terrible period of suffering and neglect, marking the beginning of a new chapter for Seven Sisters Market and Wards Corner,” says Carlos Burgos, chair of the West Green Road/Seven Sisters Development Trust.

Traders, businesses and residents formed the Development Trust to pursue a ‘community benefit plan’ as an alternative to Grainger’s corporate profit-driven scheme.

Local residents say Transport for London (TfL), as freehold owner of Wards Corner, will have to offer the Trust a long-term lease in order for a community plan to work. Colombian artist Oscar Murillo unsuccessfully tried to obtain a lease on behalf of the traders several years ago.

Mayor of London Sadiq Khan steers TfL, an executive arm of the Greater London Authority.

Restore

The Community Plan proposes to restore the existing Victorian era Wards Corner buildings – rather than demolish them as Grainger attempted.

The Plan aims to provide a café and retail space, including a new market, small business units, and a community space with a childcare centre. Other traders and businesses will be invited to rent space to ‘generate a surplus for reinvestment in other local community and enterprise initiatives in Tottenham’.

“Rooted in fifteen years of local organising, the Wards Corner Community Plan is a viable scheme to restore a heritage building and celebrated market,” says Burgos.

Firm

Haringey Council, the local planning authority, granted planning permission to the latest version of the Community Plan in 2019.

Yet Labour-controlled Haringey, under the leadership of Claire Kober (2008-18) and then Joe Ejiofor (2018-21), had always backed Grainger’s regeneration scheme.

The Council had signed a ‘development agreement’ with Grainger and first consented to the developer’s scheme in 2008. That backing held firm over ten years despite multiple legal challenges by some of the indoor market traders and Wards Corner residents.

Transfer

But Kober quit the Council in early 2018, followed by councillor Alan Strickland, Haringey’s other main cheerleader for developer-led regeneration.

Kober and Strickland lost control of the Council after local Labour Party members deselected several councillors who had backed the proposed transfer of council homes and public assets – worth billions of pounds – to the Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV). The proposed HDV was a ’50-50′ limited liability regeneration partnership between Haringey and global corporate developer Lendlease.

But a newly elected Council, led by Ejiofor, voted to scrap the HDV, saying the Council now disagreed with such an unprecedented transfer of council homes and public assets in Tottenham, Wood Green, and at Broadwater Farm. They said the HDV and these assets would likely become subordinated to the profit-seeking imperative of a corporate developer.

Lendlease and Haringey then settled out of court over the Council’s withdrawal from the HDV – with the developer saying it was ‘disappointed’ but that it would continue to ‘work together’ with Haringey on ‘High Road West’ – another Lendlease/Haringey regeneration scheme in north Tottenham.

Solution

Ejiofor, in turn, then lost the Council leadership to Peray Ahmet in an internal Labour election in late Spring 2021.

Following Grainger’s withdrawal, Ahmet, in a Council statement jointly issued with the Development Trust, says: ‘As Transport for London are the owners, we urge them to work with the Trust to co-produce a solution for the long-term future of the market.’

Standing outside the Seven Sisters Indoor Market, Ahmet added: “Latin Village is important to Haringey, Tottenham, and to people all over London.”

Hardship

A more immediate challenge for traders is to reopen the indoor market that has remained temporarily closed since the pandemic lockdown of March 2020. The Pueblito Paisa café and restaurant is open but TfL ordered the main body of the Wards Corner building closed due to fire safety concerns.

Closure has left many Latin Village traders unable to get to their shop units to make their living in the midst of the Coronavirus pandemic. They want to know if Mayor Khan will clarify whether TfL will extend an existing financial hardship scheme for traders until a temporary or permanent market is available.

TfL’s Graeme Craig says the transport body will “work with the local community and stakeholders, including Haringey Council, while we consider our potential next steps and options”.

Asset

TfL became freeholder of the Wards Corner site when the transport body took over London’s underground network in 2000. Engineers had built Seven Sisters tube station, including four Victoria Line tunnels, two escalators and a ticket hall, under Wards Corner in the 1960s.

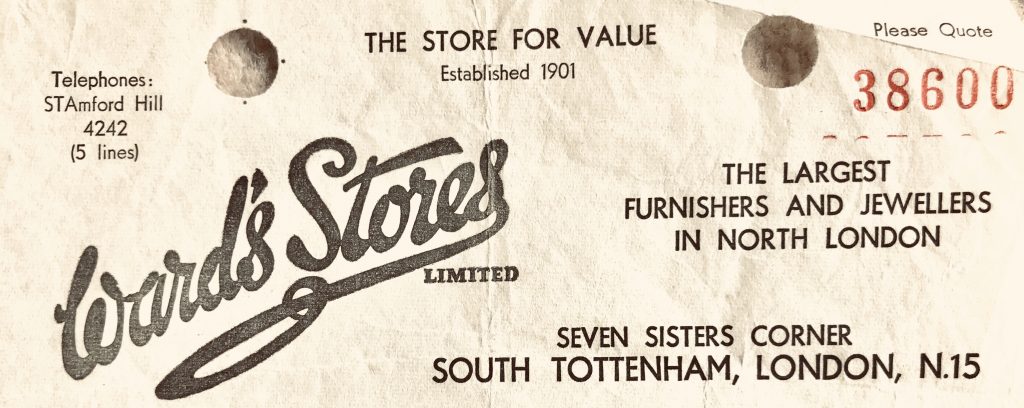

The Edwardian three-storey Wards Corner building had opened in 1901 as a landmark north London department store but closed in 1972. The main building stood neglected for some fifteen years whilst owned by London Underground Limited.

Migrants then opened the Seven Sisters indoor market on part of Wards Corner’s ground floor in the mid-1980s. Latin American traders moved in twenty years ago and the indoor market became known as the Latin Village.

People came from across London to the Pueblito Paisa restaurant to enjoy fresh empanadas, Colombian coffee, imported South American cervezas, and Latin American music and dance.

The Wards Corner ground floor area has been a listed ‘asset of community value’ since 2014.

Grainger reportedly still holds leases it had acquired across the site in pursuit of its now abandoned regeneration.

Viable

Grainger’s scheme had sought to demolish all Wards Corner buildings and re-develop the 1.65-acre site with 196 new homes, roof gardens, 15 retail and commercial units, a new indoor market, two kiosks, and a ‘public space’. Rents were estimated at £1,800-a month for its two-bedroom flats and £1,300 for one-beds.

The viability of Grainger’s scheme rested mainly on Wards Corner being right on top of Seven Sisters tube and overground rail stations. The developer envisaged prospective buyers would snap up its proposed 196 homes because residents or tenants would be able to use the Victoria Line to get to London’s West End in fifteen minutes. They would be able to commute by overground trains to and from Liverpool Street in the heart of the City of London’s financial district in just twenty minutes.

But, despite this major transport advantage, Grainger claimed in 2008 that a ‘viability’ assessment showed its regeneration scheme would not be commercially viable if the scheme provided any affordable or social/council homes. This complete lack of affordable homes stoked wider opposition to Grainger’s scheme within south Tottenham.

Local people interrogated Grainger’s regeneration scheme at several large public meetings. They pointed out thousands of lower income households on the Council’s housing register would benefit from new genuinely affordable council or social housing homes.

Condemned

Opponents also said Grainger’s Wards Corner scheme provided just six commercial units for independent traders. They believed the bulk of the proposed 3,700 square metres of commercial floorspace would be leased to chain stores, restaurants, and coffee shops – excluding Latin Village’s small independent traders.

Grainger wanted to temporarily move the indoor market with the Latin Village traders before building a new market at Wards Corner. Haringey got Grainger to agree to offer existing traders leases for equivalent stalls in such a new market.

Grainger said traders would receive money to relocate, a rent-free period in a temporary market, and a rent discount for another period in its newly built market. A significant number of traders said Grainger’s new market might cap rent rises for the first five years but market forces would hike rents up to an unaffordable level in year six.

Threat

A group of traders and residents managed – cannily it might be said – to persuade the Court of Appeal to quash Haringey’s consent for Grainger’s initial scheme. Judges ruled the Council had failed to discharge its equality duties – under the Race Relations Act 1976 – to consider the scheme’s impact on Seven Sisters’ ethnically diverse community.

Later, human rights experts from the United Nations got involved, describing Grainger’s scheme as a ‘gentrification project’ that ‘represents a threat to cultural life’.

* Gross Development Value is the estimated value that a new development would fetch on the open market if it were to be sold or rented in a similar economic climate to the current one.

Analysis

The finances of Transport for London (TfL) could dictate whether Mayor of London Sadiq Khan offers a solid proposal to Latin Village traders and Wards Corner residents.

The Labour Party’s Khan, self-styled as ‘the council house boy’, was re-elected in May 2021 for a second term. In his first-term (2016-21), Khan blamed his mayoral predecessor Boris Johnson (Conservative) for putting TfL’s finances into deficit when Johnson was mayor (2008-16).

In late 2020, Johnson, as Prime Minister, accused Mayor Khan of effectively bankrupting TfL after the coronavirus pandemic collapsed TfL’s passenger numbers and fare revenues. The result is that TfL’s enduring financial crises could leave Khan and TfL chiefs hoping to maximise returns from the transport body’s property portfolio.

Elsewhere, national rail body Network Rail, also in financial straits, has tried to claw money by maximising income from its London railway arches. Many established start-up and small businesses in Hackney, Bethnal Green and Brixton have faced being priced out of those premises.

Tacit

Grainger first coveted Wards Corner at a time when Ken Livingstone (Labour) was London’s first elected Mayor of London (2000-08).

Livingstone, campaigning in 2008 to win a third four-year term, told Wards Corner residents and Latin Village traders: “I reassure you wholeheartedly that, if I am re-elected, I will prevent Transport for London from authorising any demolition of the market until the concerns of local businesses, and users of the market, have been addressed.”

But Livingstone lost his re-election bid. Johnson actually visited the market during the 2008 campaign and said the traders and residents’ alternative plan was “brilliant” and their concerns about Wards Corner’s future under Grainger were “absolutely right”.

But, once elected mayor, Johnson gave tacit approval to Grainger’s scheme.

Superstars

Johnson, as mayor, also backed other property developer regeneration schemes across London. In June 2013, Johnson described London’s property developers as the “galacticos and superstars of the real estate industry” playing in “the most exciting game of Monopoly ever played”.

Khan too followed Johnson by giving his blessing to developer-driven regeneration schemes in his first term (2016-20). They included developer Delancey’s regeneration of the Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre in south London – a commercial and cultural hub for south London’s growing Latin American community.

Demolition of the shopping centre in 2021 has displaced Latin American traders and their customers from their long-established shops, stalls and cafés. It also means the end for a much-loved bingo hall, popular with elderly West Indian people.

Latin Elephant

Latin and Caribbean traders have battled Delancey and its backer Southwark Council to get their businesses relocated locally at the Elephant. Latin Elephant campaigners are toiling to maintain a local Latin American commercial and cultural presence – despite Delancey’s mutation of the Elephant and Castle into yet another ‘hub’ for expensive luxury flats, big brand stores, and ubiquitous chain coffee shops.

Given that Grainger are now out of the running for Wards Corner, the question is, will Khan begin his second term as London Mayor by supporting the ‘community-led plan’ that aims to secure a future for Latin American-owned businesses in north London?

Haringey

As for Haringey Council, its original intention to provide ‘affordable’ homes at Wards Corner evaporated with Grainger’s 2008 independently appraised viability assessment. Evaporation though began earlier when the Council’s original development brief of 2004 stated: ‘The amount of affordable housing should be in accordance with the policies of the Council, but will take account…of commercial viability.’

Despite the lack of affordable homes, Haringey Council has consistently pursued its development agreement with Grainger. The Council’s own scrutiny committee in 2018 stated the Council’s regeneration department should publish the amount of public money the Council has spent on Grainger’s scheme.

In 2020, then Council leader Ejiofor said, if Haringey withdrew from the agreement, Grainger would “expect to recoup millions they have already spent, and we (the Council) would still not own the land”.

Ejiofor claimed “these vital funds would be taken away from non-statutory services” such as youth provision, and support for adults and children. Even “the loss of a number of libraries” would result.

“TfL have entered into a legal commitment to sell a long lease to Grainger,” said Ejiofor. “Both parties remain committed to that deal.”

Enduring

Fast forward to 2021. Grainger are no longer committed to Wards Corner and Ejiofor is politically side-lined, for the moment.

The Council’s current leader, Peray Ahmet, can speak warmly about Latin Village on a TV news interview outside of the market. But Grainger’s withdrawal from Wards Corner does not mean the end of Haringey Council’s enduring regeneration partnerships with corporate developers.

The Council’s elected politicians and appointed officers are still actively and publicly pursuing other developer-driven regeneration schemes, including ‘High Road West’ in north Tottenham.

Grainger

Earlier in 2021, Grainger said work on the temporary market was delayed due to ‘viability challenges’. That came as a warning to some indoor market traders who had occasionally expressed a hope Grainger would see its plan through.

Grainger has tried to keep up corporate appearances in the face of its withdrawal. In its post-mortem statement, the developer claims ‘rising costs’ have forced its Wards Corner withdrawal.

Certainly, the Coronavirus pandemic and the growth of online shopping have reduced demand for ‘High Street’ shops.

Grainger claims also to have spent millions on its Wards Corner scheme. Developers, of course, can afford to throw such money, manpower, and architectural, public relations and legal resources at their London schemes.

For instance, development director David Walters exhausted much of his 14-year career at Grainger trying to convince people in south Tottenham that Grainger was not a ‘build and run’ developer. Walters left Grainger in 2017.

‘Coste’

Grainger also used GL Hearn, part of Capita, for what GL Hearn called ‘a bespoke communications and engagement strategy to support the delivery in the face of strong local opposition’. But this strategy got only pro-developer property media support kicking back against what they called a simplistic ‘social cleansing narrative’.

Grainger also hired architect Andrew Beharrell of Pollard Thomas Edwards. PTE thinly veiled Grainger’s vision as a chain store opportunity by showing it occupied by ‘Pasta Express’, ‘HCBC’ bank, and ‘Coste Cafe’.

In response to Grainger’s withdrawal, PTE stated in the Architects Journal: ‘The Grainger scheme had to be commercially self-funded. The community scheme will doubtless require significant public subsidy.’

Both GL Hearn and PTE continued to promote Grainger’s scheme online – despite Grainger’s withdrawal.

Failed

Grainger also cited the risk of ‘opening up further legal challenge’ – blaming the ‘drawn out nature of implementing the scheme owing to numerous legal challenges from a small minority’ – even though its own communications sub-contractor GL Hearn had described that challenge as ‘strong local opposition‘.

Regeneration developers across London often belittle genuine and deep-rooted opposition as a ‘small but vocal minority’. They imply a ‘silent majority’ of supporters exists locally that is cruelly being denied the philanthropic benefits of their corporately profitable regeneration.

Grainger produced a poll claiming wide local support. Many traders and residents dismissed the poll as corporate propaganda.

Despite throwing a corporate ‘kitchen sink’ at Wards Corner, Grainger did not manage to win the active support of people in south Tottenham – even with Haringey elected politicians and appointed officers spending undisclosed amounts of public money to support the scheme.

Crucially, Grainger-Haringey’s regeneration axis failed to convince most of the Latin Village traders and dozens of Wards Corner businesses and residents that regeneration offered secure tenures for their livelihoods and guaranteed futures for their families.

For instance, only one resident spoke in support of the scheme at the CPO public inquiry in 2017.

Apex

Wards Corner was meant to be part of Grainger’s ‘unrelenting focus on growing net rental income for the benefit of our shareholders’.

That focus includes Grainger’s 23-storey ‘Apex Gardens’ residential tower, built on the site of former Haringey Council offices just over the road from Wards Corner.

Grainger intended to include 39% of the Apex Gardens development’s 163 homes as ‘affordable’. Some local people though say the ‘fag packet tower’ has no socially rented homes that are genuinely affordable for families on lower incomes.

Apex Gardens is separate from Wards Corner but Grainger hoped the two schemes would have mutually raised rental and commercial values.

Time

Financially, Grainger, based in Newcastle and established in 1912, can absorb the loss of Wards Corner. Chief executive Helen Gordon announced in May the corporate developer was reporting half-year pre-tax profits of £50.3 million for 2021 and paying a total of £12.3m in dividends to its shareholders.

Corporate loss of face, though, is more difficult for developers to recoup in London’s competitive regeneration market.

Time is money for developers in that market. Grainger’s withdrawal from Wards Corner shows developers can run out of both.

Blighted

Of course, salaried developer’s employees and council officers can go home at night and forget – unlike many of the Latin Village traders and Wards Corner residents whose businesses and families have been daily affected by this twenty-year saga.

Grainger’s withdrawal means Latin Village market traders, and Wards Corner businesses and residents, can celebrate – briefly.

Shiny

What might Londoners across the city glean most from the Wards Corner saga? Perhaps, simply, to avoid judging a book by its cover.

In 2017, Sue Penny, a south Tottenham resident, referred to the neglect of the Wards Corner building being used to justify its demolition and the removal of the Latin Village traders.

‘It is therefore not surprising that people passing – who see how neglected it is – jump to the simplistic conclusion that it should be demolished and replaced with a shiny new building,’ said Penny.

**

Chronology

A sketched outline of the Wards Corner saga

· 1901: Wards brothers open Wards Department Store.

· 1972: Wards department store closes down.

· 1973: London Underground acquires Wards Corner via a compulsory purchase order.

· 1985: Migrant traders obtain leases to start to run businesses from ground floor.

· 2002: Wards Corner identified for ‘regeneration’ by the Bridge New Deal for Communities.

· 2004: Pueblito Paisa restaurant and café moves to Wards Corner. Haringey Council adopts Wards Corner/Seven Sisters Underground development brief stating ‘affordable housing…will be secured’, if ‘commercially viable’. Council shortlists four housing associations as affordable housing provider. Haringey selects Metropolitan Housing Trust to provide affordable homes. Council also selects Grainger as ‘preferred developer’. Council and Grainger continue to ‘assemble land’ for the development.

· 2006: Council identifies Wards Corner for ‘comprehensive mixed-used development’ in its adopted Unitary Development Plan.

· 2007: Grainger forms Special Purpose Vehicle to ‘deliver’ Wards Corner ‘regeneration’. Grainger enters into conditional ‘Development Agreement’ with Haringey Council. Wards Corner Community Coalition forms to oppose Grainger/Haringey scheme and devises first ‘community plan’.

· 2008: Grainger presents ‘viability’ assessment shows scheme not ‘viable’ if it includes any affordable homes. Haringey grants planning permission for Grainger scheme. Market traders and community groups submit an alternative planning application.

· 2009: High Court upholds Haringey planning consent for Grainger scheme.

· 2010: Appeal fails against ‘non-determination’ of alternative community application. Court of Appeal quashes Council planning consent for Grainger on race equality law. Haringey prepares ‘independent’ equalities impact assessment.

· 2011: Second version of ‘community plan’ produced. Riots damage properties along parts of Tottenham High Road following police shooting of Mark Duggan.

· 2012: Haringey gives planning consent to revised Grainger application, including 3,693 square metres of new retail space and 196 residential flats. Grainger and Council also sign an accompanying Section 106 agreement to ‘ensure re-provisioning of the market’ with inclusion of ‘existing traders’.

· 2013: Judicial review of the scheme. High Court rules out further appeal of the planning consent.

· 2014: Haringey Council grants planning permission to Wards Corner Community Coalition for third version of its Community Plan. Haringey lists the market as an ‘asset of community value’. Haringey publishes ‘A different type of housing market’ in its Tottenham Strategic Regeneration Framework that makes no mention of ‘council housing’. Council agrees in principle to use its CPO powers to ‘assemble’ land to allow the development to go ahead.

· 2015: Haringey- Grainger ‘development agreement’ is altered. Walters of Grainger speaks at ‘Regenerating Tottenham’ at Tottenham Town Hall. Market Asset Management leases market from TfL.

· 2016: Haringey issues Compulsory Purchase Order for remaining properties Grainger needs to proceed. 164 local people object. Grainger appoints market facilitator Quarterbridge.

· 2017: Council grants a Certificate of Lawfulness of Proposed Use or Development confirming ‘planning permission lawfully implemented’. Compulsory Purchase Order Public Inquiry held at Haringey Council. Colombian artist Oscar Murillo tries to obtain a lease but is refused. TfL publishes first report into MAM’s role as market operator. Section 106 agreement altered. United Nations Human Rights experts write to Grainger and to UK government. Planning permission for Community Plan expires.

· 2018: Planning Inspector recommends CPO should go ahead. Quarterbridge steps down as market facilitator. TfL second investigation report published saying MAM not in breach with traders. Council’s own scrutiny panel starts review of Wards Corner ‘regeneration’. Some traders resign from market Steering Group.

· 2019: Secretary of State confirms Planning Inspector’s recommendation. Haringey’s own scrutiny committee says ‘regeneration department should ‘publish money…allocated to this development’. High Court dismisses legal challenge to Secretary of State’s CPO confirmation.

· 2020: Ejiofor warns Grainger would seek “to recoup millions they have already spent” if Haringey pulls out of scheme.

· 2021: Grainger says work on temporary market delayed due to ‘viability challenges’.

· 6 August 2021: Grainger announces withdrawal from Wards Corner.

No reproduction of any of the photos used in this article is permitted without the written authorisation of the copyright owners.

© Paul Coleman, London Intelligence ® All Rights Reserved 2021