Sweets Way

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

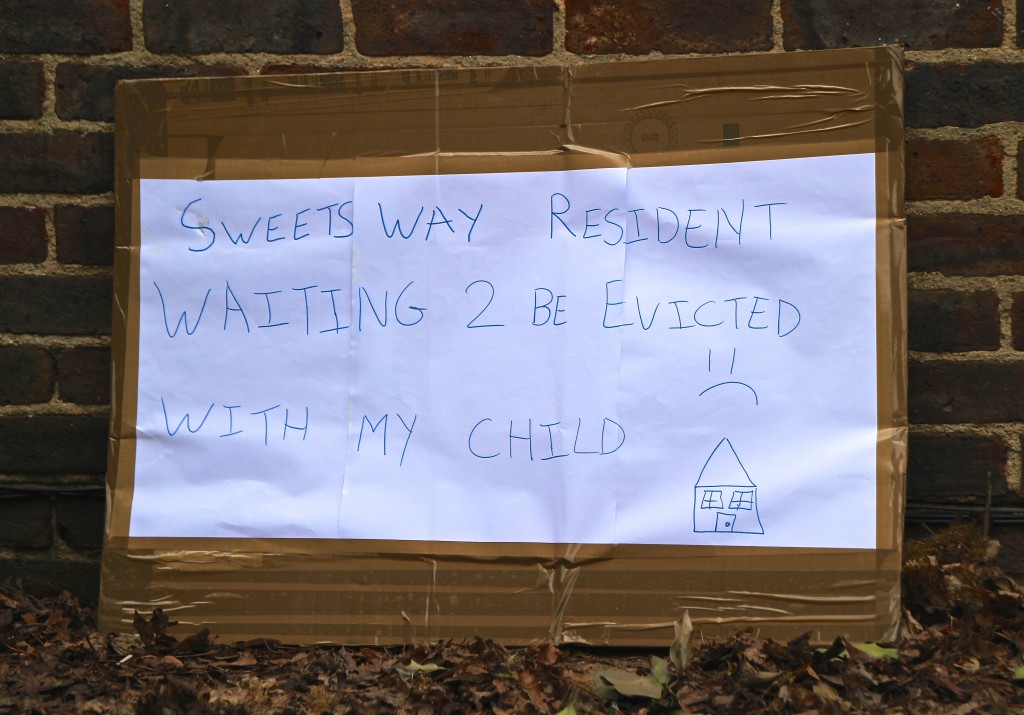

“Housing is a human right…not a privilege,” chants Kauthar, a Sweets Way resident.

But Deputy District Judge Michael Shelton doesn’t agree.

And, it’s tough for Kauthar, at the tender age of 13, to accept that the law often treats some people more equally than others.

Tougher still, Kauthar and her family have lost their home.

Decisions by a private landowner and developer – and a local authority – contribute to the family’s housing crisis.

They compel this articulate young person to spend the first day of her Easter school break protesting outside Barnet County Court in north London.

*

Rich

It’s Monday, 30 March 2015 – a day that Britain’s politicians hit the general election campaign trail.

But that political scrap might just as well be on Mars as far as Kauthar is concerned.

Kauthar and her family have lived on the Sweets Way estate for five years.

“Annington Homes and Barnet Council are breaking up our families and our community,” says Kauthar.

“They want to knock down those houses which are in perfect condition.

“They’re taking us far away from our friends and families.

“They are evicting us from our homes because we are poor.

“If we were rich they wouldn’t be doing this.”

*

Vast

But Annington is rich, owning almost 42,000 homes across England and Wales.

These homes used to belong to the Ministry of Defence.

The MoD used them to house service families.

Annington acquired this vast estate in 1996 and leased them back to the MoD.

It sells these homes when the MoD no longer needs them.

Private equity investment house Terra Firma acquired Annington Homes for £3.2 billion in 2012.

Terra Firma chairman Guy Hands said: “Annington is a pure play UK residential property company with a blue chip tenant and with the ability to benefit from the strength of the property market.”

Hands, 55, and wife Julia, reportedly enjoy wealth estimated at £250 million.

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

Social cleansing

Sweets Way is just one of over 50 council or social housing estates across London facing developer-led demolition and redevelopment.

Endorsed by local politicians, seductively guised as ‘regeneration’, these schemes result in the net loss of council or homes for social rent.

New homes built over these estates are sold on London’s over-heating property market.

They go for prices way beyond the means of Londoners on average and lower incomes.

Sweets Way’s planned new market sales homes could command values of up to £1 million – especially with foreign investors looking to buy London homes close to commuter stations. The estate is close to Totteridge & Whetstone tube station.

The small proportion of planned new ‘affordable’ homes – shared ownership and shared equity – are also likely to be unaffordable for most people on average incomes, let alone less affluent Londoners.

Social housing campaigners say Sweets Way typifies how London is rapidly becoming the global capital city of ‘social cleansing’.

Poorer people on low incomes and benefits are decanted, evicted and displaced to outer suburbs and many – facing the ‘bedroom tax’ and capped benefits – are compelled to take offers of housing in other cities and towns way outside of London.

This has led to accusations that politicians and developers are turning London into a city exclusively for the wealthy.

*

Human right

Inside the full courtroom, the judge, Michael Shelton, sports a pinstripe suit and a calm yet flamboyant air.

Shelton is a part-time deputy district judge in the family and civil section of the London Group of Courts.

He is a member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, Secretary General of the International Dance Sport Federation and Director of the Sylvia Young Theatre School.

Shelton is also vice-chairman of the Harrow Churches Housing Association, which describes itself as ‘a small and growing housing association serving vulnerable people in the London boroughs of Harrow, Hounslow and Hillingdon’.

*

Public

“I really don’t think the human rights point is valid at all,” says Shelton.

He says UK human rights law simply does not apply to private bodies.

Shelton addresses his remarks to Ella Harris, the only named of three defendants served with a possession order by Annington Homes, Sweets Way’s private landowner and developer.

Harris represents herself and other Sweets Way protesters, including ex-residents, like Kauthar.

She reads quickly and slightly nervously from a prepared script.

“Slow down, please,” says Shelton. “I need to make notes and don’t do shorthand.”

Harris counters Shelton by saying his civil court is “a public body and has a duty of care to members of the public”.

But Shelton explains: “This is a court of law.”

*

Belt and braces

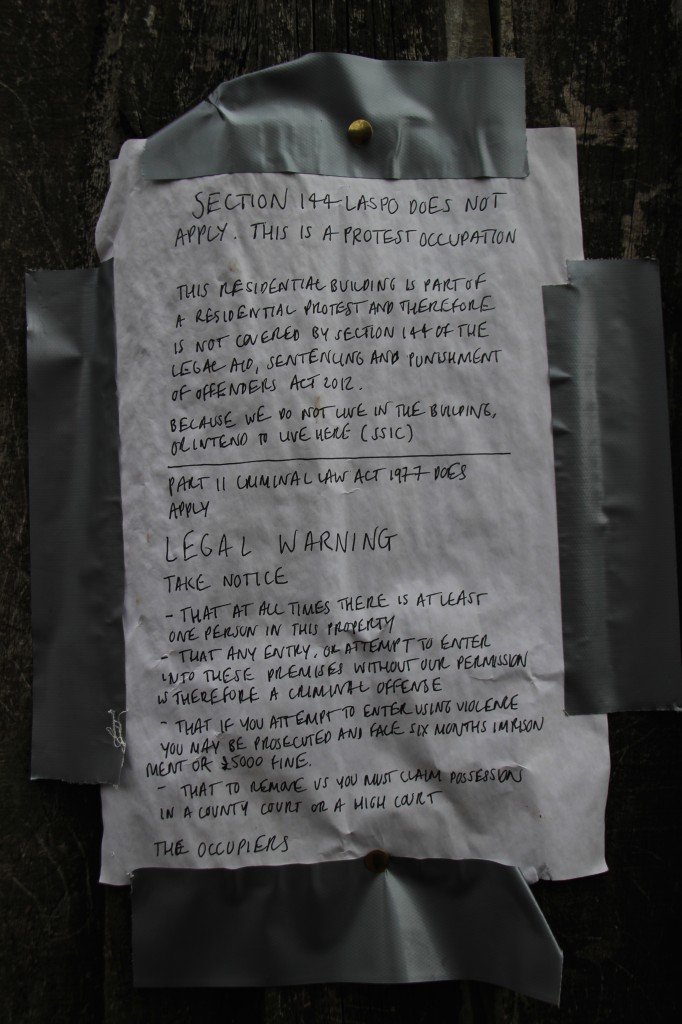

Harris argues the possession order and injunction are “excessive and draconian measures against the right to peacefully protest”.

“The possession order and extreme width of the injunction imposes criminal sanctions against families, including single mothers with young children,” contends Harris.

“People should be allowed to protest on land which is part of their community and where their children’s schools are based.

“Even the police say this response is disproportionate.

“Police said it was a lawful protest and a civil matter.”

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

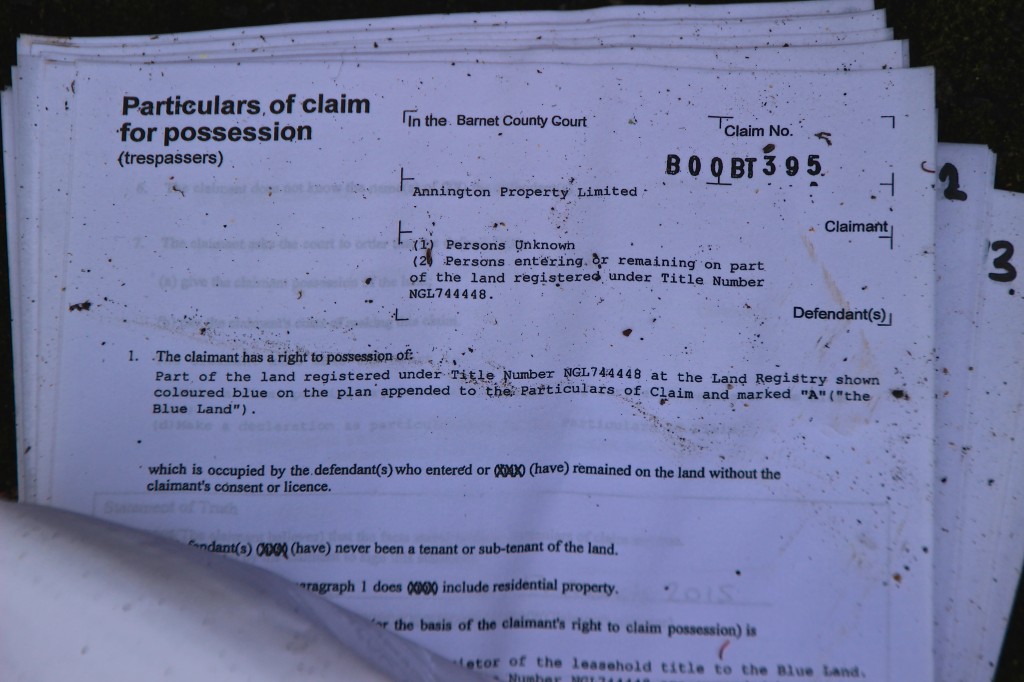

‘Blue Land’

Counsel for Annington Tom Roscoe invites Shelton to look at the ‘Blue Land’ marked on a map of Sweets Way.

The ‘Blue Land’ is a large swathe of Sweets Way targeted by the possession order and the injunction.

“I’m colour blind,” quips Shelton, straightening his blue tie emblazoned with a bizarre yellow scrawl.

Roscoe argues a pre-emptive ‘belt and braces injunction’ covering Sweets Way’s entire 160 homes “would deter people from entering the site”.

“This is one development site, not 150 different properties,” says Roscoe.

“Annington would not have to send bailiffs to re-execute the possession order in the event of other properties being occupied by protesters.

“It would avoid a ridiculous merry-go-round of evictions.”

*

Plans

Harris and two other defendants were served with possession orders after they and other protesters occupied six empty Sweets Way homes.

Land and homeowner Annington want to move all residents to make way for a new, ‘mixed’ and more densely populated development.

The quiet, enclosed estate with no through traffic consists of neat blocks of well-built, spacious houses with gardens.

The blocks of homes are separated by large expanses of grass.

Sweets Way is also full of mature trees.

There’s a playground and car parking but no fast food shops nor advertising billboards.

In relative urban terms, it’s a tranquil backwater.

Maybe even a throwback to the 1960s and 1970s.

But, in the last five or six years, Sweets Way became a home and neighbourhood for hundreds of London families with lower than average incomes.

*

Increased

Annington says the Ministry of Defence no longer needed the homes and began handing them back in 2008.

Annington then entered into detailed discussions with Barnet Council and the Greater London Authority to redevelop Sweets Way with an increased number of ‘new, better designed homes’.

But this planning and discussion takes six years.

During this period, Annington decides to make some money from Sweets Way and lets the existing homes on a ‘temporary basis’.

Annington let some homes to tenants through Touchstone, a lettings agent.

Some are let to Notting Hill Housing, one of London’s largest housing associations.

NHH then sub-lets these homes and asks Barnet Council to nominate families from the council’s waiting list to live at Sweets Way.

Since then, many families, including Kauthar’s, have made Sweets Way their home.

Whetstone, a quiet corner of Barnet, becomes their neighbourhood for schools, nurseries, doctors and shops – and the area where they develop family and social ties.

Sweets Way, although privately owned and earmarked for development, becomes a precious part of London’s social housing provision for a small yet significant number of Londoners on average and lower incomes.

*

Communicated

Yet Annington says since 2009 ‘it has always been made clear to all tenants that these were temporary lets’ and that redevelopment was always likely.

‘Since July 2014 every tenant has been communicated with regularly and has known that they would need to vacate in January 2015,’ says Annington.

In December 2014, Barnet Council grants Annington Homes planning consent to demolish Sweets Way’s existing 160 homes and redevelop the estate.

Hence, Annington seeks vacant possession to prepare the site.

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

Lightning

Residents say the eviction has been badly handed.

Families are asked to leave between 9 February and 23 February.

This ‘lightning’ eviction and property clearance sends several families into turmoil.

Several are Turkish and Kurdish, including refugees.

Moving from two and three-bedroom homes into cramped temporary accommodation means they have to leave their belongings and furniture behind.

They cannot afford £130 monthly storage costs.

Some residents say Barnet Council allowed them to keep their fridges and washing machines inside their Sweets Way homes whilst they searched for permanent accommodation.

But some emptied homes are reportedly burgled and items stolen.

*

Temporary

Other Sweets Way families approach Barnet Homes, the body managing Barnet’s 15,000 council homes.

Barnet Homes says it has rehoused 32 of these families in Barnet and three in neighbouring Brent.

Another 14 households living at Sweets Way on a ‘long-term temporary basis’ are offered ‘alternative temporary accommodation prior to their eviction’.

Some are reportedly sent to other boroughs like Enfield, Waltham Forest and Westminster.

Others are sent out of London, to Luton and parts of Essex.

*

Lost friends

Manal Mahadi has lived on Sweets Way for five years.

She says these ‘temporary’ arrangements are putting a huge strain on her family, including her two children.

Initially, Barnet Homes moved the Mahadi family 13 miles from Whetstone to Westminster.

Leanne, Mahadi’s 12-year-old daughter, her voice shaking, says: “My parents have been with the Council for over 16 years.

“We were given a temporary house in Westminster but my school is in Friern Barnet. It takes me over one hour to go by bus to school.

“I get travel sick on the bus.

“I made loads of friends here at Sweets Way and it’s really easy to get to school.

“But I’ve lost loads of my friends because I’ve had to go to different secondary schools because of this housing situation.

“I feel really upset and that the Council just don’t care.

“It feels like they could chuck us on the street and not care.

“They are heartless.”

After the 30 March hearing, Mahadi says Barnet Homes have since moved the family to the Grahame Park Estate in Colindale.

“But they’re going to knock down that place too soon,” says Manal.

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

Regrettable

Take a look around the estate and inside the homes.

Sweets Way’s 160 homes are in good structural and decorative condition.

Yet they face ‘soft-stripping’ and demolition.

Doors and windows are ‘tinned’ with metal screens by Orbis, a contractor specialising in securing sites being readied for demolition and re-development.

Annington offers the standard litany offered by developers pursuing a redevelopment.

A spokesman reads a statement: ‘Annington very much supports the argument for more homes in London, although there is a need for development to achieve this.

‘It is regrettable when homes need to be demolished.

‘But Annington’s decision to redevelop the estate will see an increase in the number of homes.’

*

Rebrands

By February 2015, Annington is ready to demolish Sweets Way’s 160 homes and redevelop the estate with up to 288 new homes.

The vast majority – 229 – will be offered for private sale on London’s over-heating property market.

Higher-than-average income buyers are Annington’s target market, especially those who commute to London’s West End and the City financial district.

Annington even rebrands Sweets Way as ‘Sweets Way Park’, typical of such up-market ‘regeneration’ schemes across London.

*

Offered

Annington says it will offer 59 of the 288 new homes, or 20%, as ‘affordable’.

Twenty-six of these 59 will be offered as ‘shared ownership’ – part-buy and part-rent.

The remaining 33 are to be offered as ‘affordable rent’ – meaning tenants might have to pay up to 80% of the local average market rate.

None will be offered as social housing, at rents equivalent to council rents.

*

Occupation

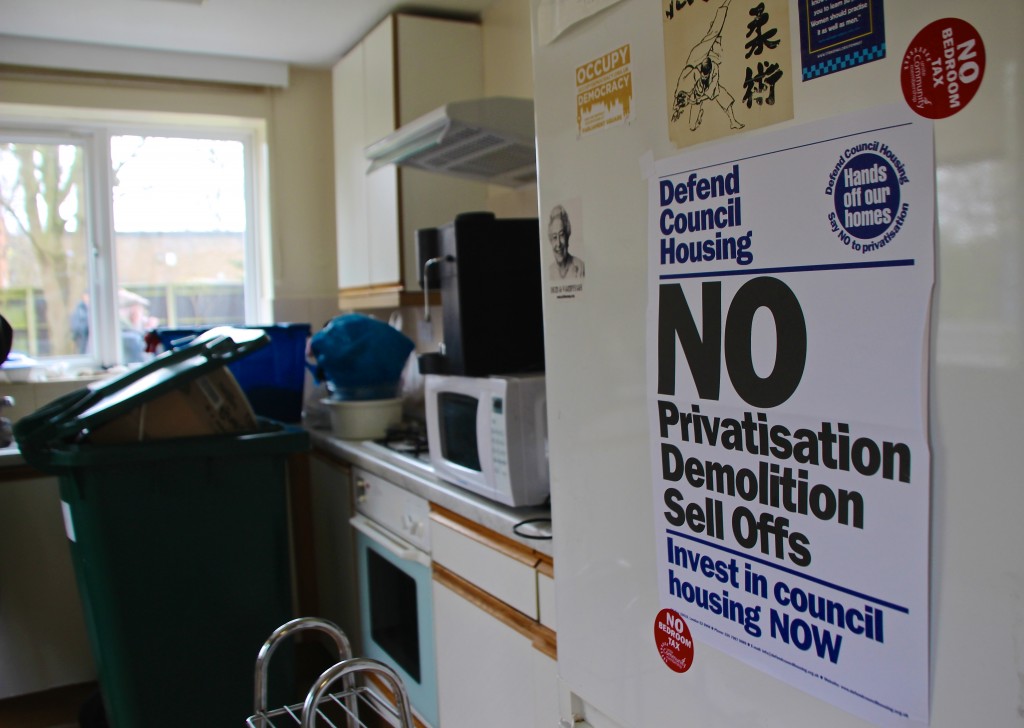

Annington’s plan outrages enough residents to prompt an occupation of emptied homes by some tenants and their supporters on 8 March.

They include social housing activists from other estate campaigns across London.

Protesters remove the metal screens to enter six homes.

Local resident Rose de Souza says: “It feels like a little revolution.

“They’re destroying communities as they’re moving children away from their schools.”

“It’s social cleansing.

“It seems only property developers can have houses now and rent or sell them to very rich people.

“People don’t matter, just profit.”

*

Peaceful

60 Sweets Way becomes the focus of the occupation.

Residents and campaigners turn this house into a ‘community centre’.

On 17 March, the occupiers stage a ‘sleepover’.

They receive a supportive visit from Russell Brand, an increasingly politically active London comedian.

The protesters number 20 or so at any one time.

The police say their action constitutes a peaceful protest.

There are no incidents of obstruction or criminal activity.

*

Compelled

Protesters want existing council estates and homes used for social housing to be saved from demolition.

They say developer-led ‘regeneration’, of the kind endorsed by local councils across London, leads to public housing being replaced by luxury homes that Londoners on average and lower incomes simply cannot afford.

Less affluent and poor Londoners, says Harris, are being forced out of their neighbourhoods.

Away from their schools, nurseries, doctors, families, friends and familiar neighbourhoods.

Compelled to move to temporary accommodation in other boroughs.

And, finally, even faced with the possibility of having to take the first offer from local councils of ‘suitable alternative accommodation’ in a city or town outside of London.

Either accept that offer, or be told refusal means they’ll be considered as making themselves ‘intentionally homeless’ – and are no longer the responsibility of any public housing authority.

*

Worsens

Back in court, Shelton issues his judgment.

Shelton says no tenants remain with a right to be living on Sweets Way.

“Sadly, for the people occupying various properties, there is no basis in law whatsoever to deny Annington Homes’ right of possession,” says Shelton.

“I have listened carefully to the defendants’ arguments. But they don’t, I’m afraid, hold up.

“I can understand why the properties have been occupied.

“But the occupation must end.

“The occupiers have no right to be there and I must authorise enforcement forthwith.”

*

Social

Shelton returns to the issue of housing as a human right, and chips in a further comment that irks Harris and fellow Sweets Way protesters.

“I can’t see any human rights arguments whatsoever,” emphasises Shelton.

“Annington is a not a public body.

“Yet Annington has used the land to provide social housing.

“The estate was not left barren for eighteen years.

“I don’t see many such bodies doing that.”

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

Future

Harris and fellow occupiers then receive a further blow.

Shelton rules that she must pay £3,163 legal costs.

Annington hopes this award will deter future protest occupations.

But, just a few hours after Shelton’s ruling, a group of protesters and residents, including Kauthar and her mother – and Ella Harris – are back at Sweets Way.

They watch as other protesters move sprightly from the properties subject to Annington’s possession order to another neat home on the northern fringe of the estate (above). Annington own the home but campaigners say it is ‘just beyond the injunction and possession zones’.

Katya Nasim, a housing activist, says Sweets Way is the third estate in London to be occupied in 2015 in protest against demolition and ‘regeneration’ following similar actions on the Aylesbury Estate in Walworth and the Guinness Trust’s Loughborough Park estate in Brixton, south London.

Residents are also taking direct action to block construction vehicles on the West Hendon Estate in north-west London.

“There is a sense we’re in crisis and that we can take our houses back,” says Nasim.

*

© London Intelligence 2015

*

Emergency

Speaking to London Intelligence, Kauthar explains: “Because of Annington, Barnet Council have sent my family – my Mum, my brother, my Dad and I – to Enfield.

“It takes my brother and I an hour and a half just to get school.

“We need to wake up at five in the morning.

“They put us in emergency accommodation.

“When we first arrived the door wouldn’t lock.

“You didn’t need a key.

“We still don’t have hot water to this day from the shower.

“And there’s no proper heating.

Help

“My Dad has just come out of hospital with mental health problems.

“He’s had seven operations since last September.

“My Dad can’t climb up and down up the stairs.

“My mother has like three jobs.

“She works in a coffee shop.

“Then she looks after my Dad.

“And then she looks after us – her kids.

“The Council once told my mother she must work in order to get help.

“But now she works – and we still don’t get any help.

Strong

“It takes Mum more than an hour to get to work.

“And my brother and I spend like half of our day just travelling to and from school.

“By the time we get home, we’re too tired to even eat sometimes.

“We used to have a really strong community on Sweets Way.

“If my Mum had to take my Dad to hospital, she could leave us with our neighbours because she knew they’d take care of us.”

“People are not taking this anymore,” says Kauthar.

“Housing is a human right and we’re fighting back.”

*

*

© Paul Coleman, London Intelligence, 2015